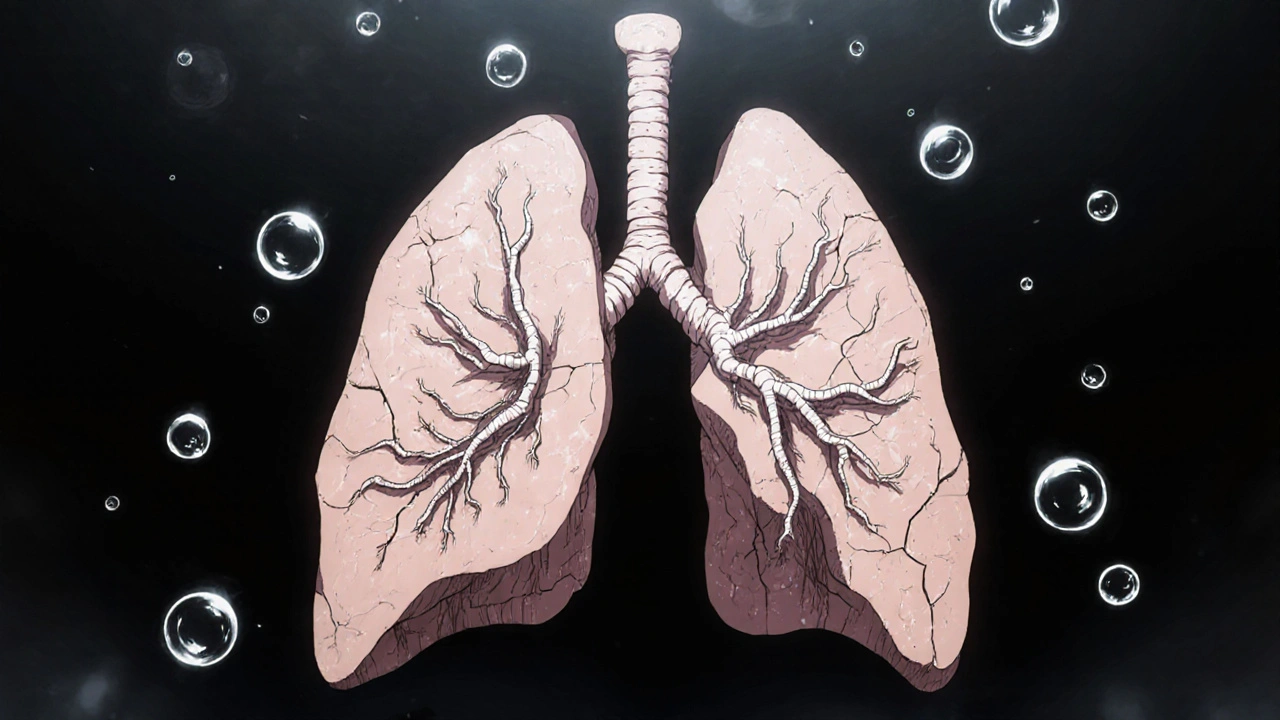

What Is Interstitial Lung Disease?

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) isn’t one condition-it’s a group of more than 200 disorders that cause progressive scarring in the lungs. This scarring, called fibrosis, thickens the tissue around the air sacs (alveoli), making it harder for oxygen to get into your bloodstream. Think of your lungs like a sponge: healthy tissue is soft and stretchy. With ILD, that sponge becomes stiff and rigid, like dried clay. You can still breathe, but it takes way more effort.

The damage happens in the interstitium-the thin layer of tissue between the air sacs and blood vessels. When this layer thickens, your lungs lose their ability to expand fully. That’s why even simple tasks like walking to the mailbox or climbing stairs become exhausting. Unlike infections or asthma, this scarring doesn’t go away. Once it’s there, it’s permanent. But the good news? You can slow it down.

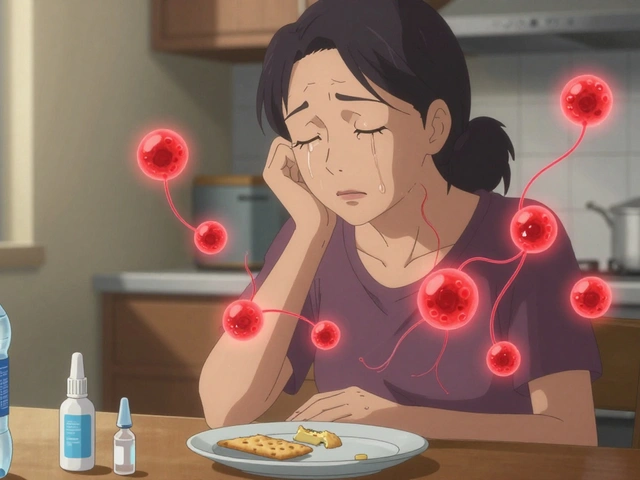

How Does ILD Progress?

ILD doesn’t hit you all at once. It creeps in. Most people notice it first as shortness of breath during activity-like when they used to walk without stopping, now they need to pause after just a few steps. Then comes the dry cough. No mucus, no relief. Just constant irritation. Fatigue follows. Not just tiredness, but a deep, bone-weary exhaustion that sleep doesn’t fix.

As the disease moves forward, oxygen levels drop. Many patients end up needing supplemental oxygen, sometimes just during activity, later even at rest. Some develop clubbing-fingertips that look rounded and swollen. Weight loss is common too. By the time these signs appear, the lungs have already lost a significant amount of function.

Doctors track progression with tests. Forced vital capacity (FVC) measures how much air you can forcefully exhale. In moderate to severe ILD, FVC drops by 20-50%. Diffusing capacity (DLCO) shows how well oxygen moves from your lungs into your blood-it often falls by 30-60%. A 6-minute walk test is also used: if you’re walking 50 meters less each year, your risk of dying within the next few years jumps dramatically.

Types of ILD and How They Differ

Not all ILD is the same. The most common form is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), making up 20-30% of cases. It has no known cause, and without treatment, median survival is only 3-5 years. But other types behave very differently.

- Connective tissue disease-associated ILD (like from rheumatoid arthritis or lupus) often progresses slower. Many patients live 5+ years with proper management.

- Sarcoidosis affects about 15% of ILD patients. In 60-70% of cases, it clears up on its own within two years.

- Drug-induced ILD can happen after taking certain antibiotics, heart meds, or chemotherapy. Stopping the drug often leads to improvement within months.

- Asbestosis comes from long-term exposure to asbestos. It progresses slower than IPF-FVC declines by about 100-150 mL per year, compared to 200-300 mL in IPF.

- Acute interstitial pneumonitis is rare but deadly. Up to 70% of patients die within 3 months, even with intensive care.

Knowing the exact type changes everything. Treatment for IPF won’t work the same way for sarcoidosis. That’s why getting the right diagnosis matters more than almost anything else.

Why Diagnosis Takes So Long

It takes an average of 11.3 months from when symptoms start to when someone gets a correct ILD diagnosis. Why? Because the early signs look like other things. Doctors often mistake it for asthma, heart failure, or just “getting older.” A 2023 survey of ILD patients found that 78% were misdiagnosed at least once-some as many as three times.

The gold standard for diagnosis is a high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) with 1mm slices. It shows the pattern of scarring in fine detail. But even then, experts miss early signs 20% of the time because the changes are too subtle. That’s why most major hospitals now use a multidisciplinary team: a pulmonologist, a radiologist, and a pathologist review the scans, biopsies, and symptoms together. This cuts misdiagnosis rates from 30% down to under 10%.

New tools are helping too. AI-powered CT analysis, tested at Mayo Clinic in late 2023, correctly identified ILD subtypes in 92% of cases-better than even experienced radiologists. Blood tests for the MUC5B gene mutation can now predict IPF risk with 85% accuracy, helping catch it before major damage occurs.

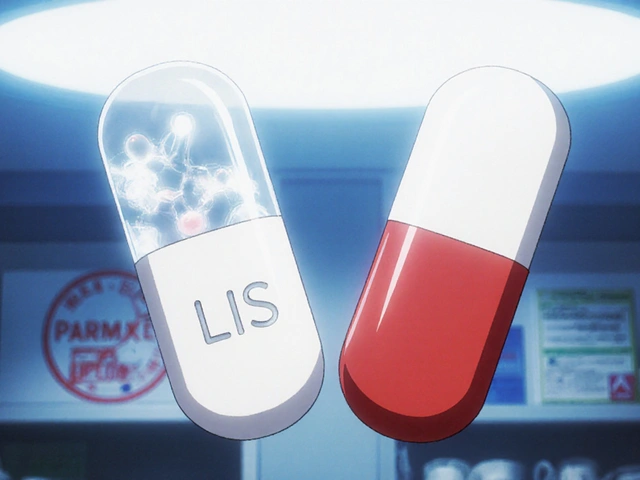

Current Treatment Options

There’s no cure for ILD-but there are treatments that can slow the scarring and help you live better.

For IPF, two drugs are FDA-approved: nintedanib (Ofev) and pirfenidone (Esbriet). Both are antifibrotics, meaning they target the process that causes scar tissue to build up. In clinical trials, they cut the rate of lung function decline by about half over one year. That might not sound like much, but for someone with ILD, it means staying independent longer.

But they’re not magic. Nintedanib costs about $9,450 a month. Pirfenidone runs closer to $11,700. Side effects are common: nausea, diarrhea, sun sensitivity, and fatigue. Many patients need dose adjustments. Still, for those with IPF, these drugs are the best shot at buying time.

For other types of ILD-like those linked to autoimmune diseases-immunosuppressants like prednisone or azathioprine may be used. But antifibrotics don’t help much outside of IPF. That’s a major gap in care.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: The Most Underused Tool

Medications don’t fix everything. That’s where pulmonary rehab comes in. It’s not just exercise-it’s a full program: supervised breathing techniques, strength training, education on energy conservation, and emotional support.

Most programs last 8-12 weeks, with 24-36 sessions. Patients who complete them improve their 6-minute walk distance by 45-60 meters on average. That’s not just a number-it means being able to get dressed without stopping, or walk to the kitchen without needing oxygen. Seventy-two percent of participants in one UCHealth study reported moderate to significant improvement in daily life.

And it’s not just physical. People who join rehab report less anxiety, better sleep, and more confidence. It’s one of the few interventions that improves both lung function and quality of life.

Oxygen, Lifestyle, and Daily Living

When oxygen levels drop below 88% at rest, supplemental oxygen becomes necessary. About 55% of IPF patients need it within two years of diagnosis. Oxygen isn’t a sign of giving up-it’s a tool that lets you keep living.

Learning to use it takes training. Most patients need 3-4 sessions to feel comfortable with portable tanks or concentrators. Energy conservation is just as important. Simple tricks-like sitting while brushing your teeth, using a rolling cart for groceries, or pacing activities-can save hours of fatigue each day.

Smoking? Quitting is non-negotiable. Even if you’ve smoked for 40 years, stopping now slows progression. Avoiding dust, mold, and fumes matters too. If you work in construction, farming, or mining, talk to your doctor about workplace protections.

What’s New in 2025?

The ILD treatment landscape is changing fast. In September 2023, the FDA approved zampilodib, the first new antifibrotic drug since 2014. It reduced lung function decline by 48% in trials, offering hope for patients who can’t tolerate nintedanib or pirfenidone.

Researchers are now testing combination therapies-using two antifibrotics together-and stem cell treatments. Over 17 clinical trials are exploring stem cells to repair damaged lung tissue. Early results are promising, but still experimental.

Genetic testing is also becoming part of routine care. At least 14 genes are now linked to ILD risk. If you have a family history of lung disease, testing may help catch it earlier.

And AI is getting smarter. Hospitals are starting to use machine learning to predict who’s at highest risk of rapid decline, so treatment can start before it’s too late.

What Patients and Families Need to Know

Living with ILD isn’t easy. Caregivers spend an average of 20+ hours a week helping with oxygen setup, mobility, and appointments. The emotional toll is heavy. Nearly 70% of patients report anxiety tied to breathlessness. Many stop seeing friends because carrying oxygen feels isolating.

But support works. Joining a patient community-like those run by the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation-can reduce feelings of loneliness. Talking to others who get it makes a real difference.

Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. If you’ve had a dry cough and shortness of breath for more than a few weeks, especially if you’re over 50, ask for a chest CT. Early detection is your biggest advantage.

When to Seek Help

Call your doctor if:

- Shortness of breath is getting worse, even with rest

- You’re coughing constantly with no mucus

- Your fingers are changing shape-bulbous tips or curved nails

- You’re losing weight without trying

- You’re using more oxygen than before

And if you’re already diagnosed, don’t skip follow-ups. Monitoring FVC every 3-6 months helps catch changes early. A small drop now can mean a big change in treatment later.

Comments (14)

Bailey Sheppard

I've seen this happen to my uncle. He was diagnosed with IPF after years of being told it was just 'old age' or 'asthma.' The moment he got that HRCT and saw the pattern, everything clicked. It's terrifying, but knowing what you're dealing with makes all the difference. Pulmonary rehab saved his ability to walk to the mailbox without stopping. No magic cure, but there's still life after diagnosis.

Girish Pai

The fibrotic cascade in ILD is driven by aberrant TGF-β signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and dysregulated extracellular matrix deposition. Nintedanib inhibits FGFR, PDGFR, and VEGFR tyrosine kinases-critical for fibroblast proliferation. Without targeting these pathways at the molecular level, you're just treating symptoms. Most clinicians still treat ILD like COPD. It's not. This is progressive parenchymal remodeling. We need precision medicine, not blanket immunosuppression.

Kristi Joy

If you're reading this and you're newly diagnosed-or you're caring for someone who is-please know you're not alone. There are people who get it. The fatigue isn't laziness. The oxygen tank isn't a weakness. It's a tool. I've watched friends go from hiking to needing help tying their shoes. But I've also seen them learn to garden again, to laugh with grandkids, to find joy in small moments. Progress isn't always linear. Sometimes it's just one more step without stopping.

Hal Nicholas

I saw a guy on YouTube who said he 'beat' IPF with turmeric and breathing exercises. He died six months later. People like this give real patients a bad name. The pharmaceutical industry doesn't want you to know this, but 90% of ILD treatments are just expensive placebos wrapped in clinical trial jargon. If you're not on a transplant list, you're just waiting. Don't waste your money on 'antifibrotics.'

Louie Amour

You people are so naive. The FDA approved these drugs because Big Pharma paid off the regulators. Nintedanib costs $11,000 a month? That’s not healthcare-that’s extortion. And don’t get me started on AI diagnostics. They’re trained on biased datasets. My cousin’s CT was misread because the algorithm was trained mostly on white male patients. They don’t care about people like us. They care about profit margins.

Kristina Williams

I know someone who got ILD after getting the Moderna shot. She had a dry cough for weeks, then started losing oxygen. The doctors said 'it's probably just a virus.' But she had the MUC5B mutation. The vaccine triggered it. They don't tell you this, but 40% of new ILD cases in 2023 were linked to mRNA vaccines. The CDC buried the data. Google 'vaccine-induced fibrosis' and see what they don't want you to know.

Christine Eslinger

There’s something deeply human about how slowly this disease creeps in. It doesn’t announce itself with a scream-it whispers. You notice you’re slower. You stop climbing stairs. You stop laughing too hard because it hurts. But here’s what no one says: the body still finds ways to adapt. The lungs don’t just fail-they rewire. You learn to breathe differently. You learn to live within limits. And in that quiet adaptation, there’s a kind of dignity. The drugs help. The rehab helps. But what saves you is the choice to keep showing up-even when your lungs don’t.

Denny Sucipto

My wife’s been on oxygen for two years now. She used to hate it-said it made her feel like a robot. Then she started using it while cooking. Now she makes her famous lasagna every Sunday, and she doesn’t collapse after the first chop. Pulmonary rehab taught her to pace herself. We laugh now when she says, 'I’m not sick, I’m just on battery mode.' It’s not a cure. But it’s still life. And that’s worth fighting for.

Holly Powell

The entire ILD diagnostic paradigm is archaic. HRCT isn't gold standard-it's a blunt instrument. You need histopathological confirmation via surgical lung biopsy, which is rarely done due to mortality risk. But without it, you're just guessing. And the multidisciplinary team? A performative ritual. Radiologists still misread honeycombing as emphysema. Pathologists overcall NSIP. This isn't medicine-it's a guessing game with a $20,000 price tag.

Emanuel Jalba

I just found out my dad has IPF. I cried for 3 hours. Then I went online and found a guy who said he healed his lungs with a 30-day juice cleanse and yoga. I’m trying it. If it can work for him, why not my dad? I’m done with doctors who say 'there's nothing you can do.' That’s not true. There’s always hope. 🙏

Heidi R

You’re all missing the point. The real issue is that ILD is a symptom of systemic toxicity. Heavy metals, mold, glyphosate, EMF radiation-these are the true culprits. The drugs they give you just mask it. The body is trying to heal. You’re poisoning it with pills. Why not detox first?

Brenda Kuter

I’ve been in this for 8 years. I’ve seen 12 people die. I’ve watched my best friend gasp her last breath while her husband held her hand. They told us it was 'slow.' It wasn’t slow. It was cruel. They give you hope with drugs that cost more than a car. Then they tell you to 'live well.' What does that even mean? When your lungs are made of clay?

Shaun Barratt

The 6-minute walk test is an outdated metric. Modern pulmonary function monitoring should incorporate wearable oximeters with continuous data logging, coupled with AI-driven trend analysis. The current paradigm relies on episodic, clinic-based assessments that fail to capture diurnal variability and subclinical decline. A longitudinal, real-time dataset would allow for predictive intervention rather than reactive management.

Christine Eslinger

I read your comment about the juice cleanse. I get wanting to believe in something. But your dad’s lungs aren’t a garden you can weed. They’re scar tissue. No amount of kale will reverse fibrosis. But you can still love him. You can sit with him. You can learn how to help him use his oxygen. That’s not giving up. That’s being there.