When someone is diagnosed with HIV today, the news doesn’t mean a death sentence. It means starting a daily routine with medications that keep the virus under control-often for life. But behind that simple routine is a complex science of drug interactions, resistance mutations, and carefully balanced regimens. Get one thing wrong, and the virus can bounce back stronger than before.

How Antiretroviral Drugs Actually Work

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) doesn’t cure HIV. It stops it from multiplying. There are six main classes of these drugs, each targeting a different stage of the virus’s life cycle. NRTIs and NNRTIs block reverse transcriptase, the enzyme HIV uses to copy its RNA into DNA. Protease inhibitors stop the virus from cutting its proteins into usable pieces. Integrase inhibitors prevent HIV from inserting its genetic material into human DNA. Fusion inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists keep the virus from even entering immune cells.

The goal? Reduce the viral load to undetectable levels-below 50 copies per milliliter of blood. When that happens, the immune system can recover, and the person can’t transmit HIV to others. This isn’t theory. It’s standard practice. Since 1987, when zidovudine (AZT) became the first approved drug, we’ve gone from one pill a day with brutal side effects to single-tablet regimens that are easier to take and far safer.

Why Resistance Happens-and Why It’s So Dangerous

HIV mutates fast. Every time it copies itself, errors creep in. Most of those errors kill the virus. But some? They let it survive even when drugs are present. That’s resistance.

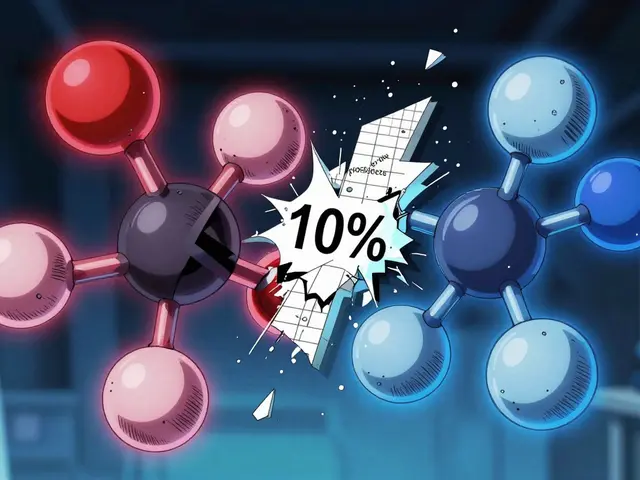

Take lamivudine or emtricitabine, two common NRTIs. A single mutation-M184V-can make them useless. That’s why they’re never used alone. They’re always paired with other drugs. The same goes for efavirenz, an older NNRTI. One mutation, K103N, and the whole class can fail. That’s why newer NNRTIs like doravirine were developed. They’re designed to hold up even when those common mutations are present.

INSTIs like dolutegravir and bictegravir are the strongest weapons we have. They need multiple mutations to lose effectiveness. In clinical trials, only 0.4% of people starting dolutegravir developed resistance after 144 weeks. Compare that to efavirenz, where the rate was over 3%.

But resistance isn’t just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. Miss a dose. Skip a few. Delay refills. That’s when subtherapeutic drug levels build up. The virus gets just enough pressure to adapt-but not enough to die. That’s how resistance starts quietly, often without symptoms, until a routine test shows the viral load creeping up.

Drug Interactions: The Hidden Threat

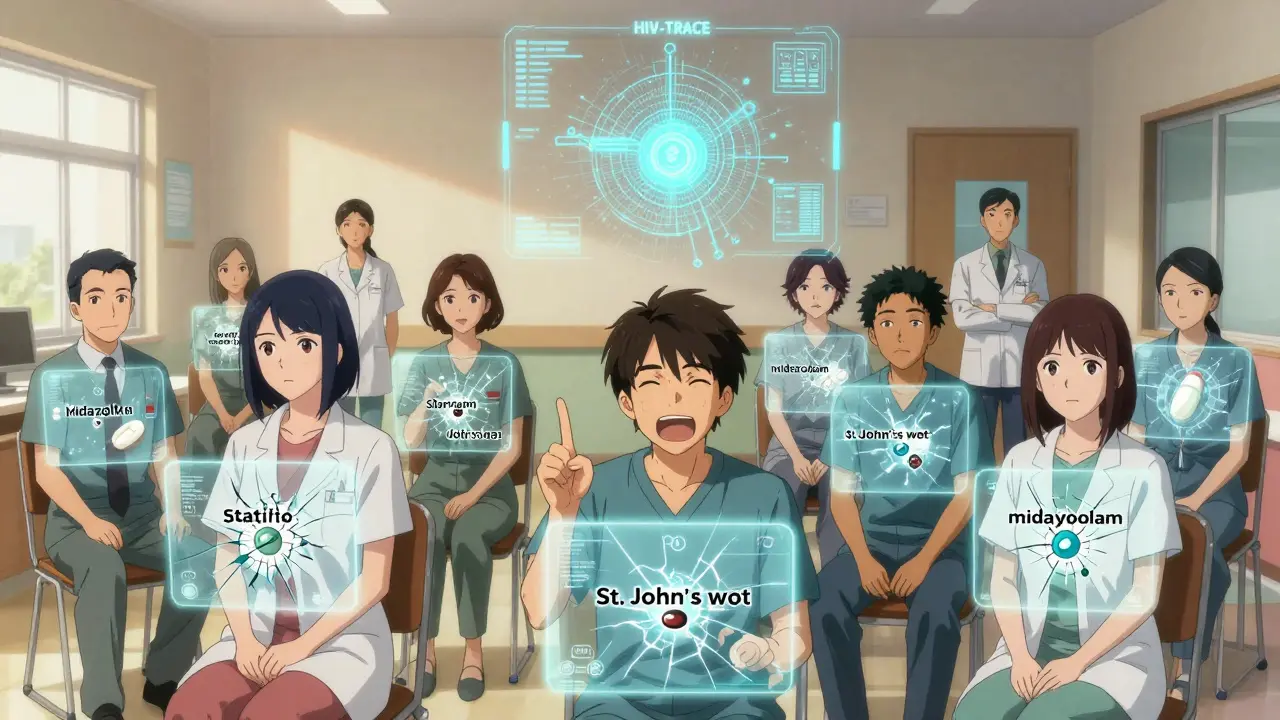

Most people with HIV don’t take just one medication. They take blood pressure pills, cholesterol drugs, antidepressants, pain relievers, even supplements. And many of those interact dangerously with HIV drugs.

Boosted protease inhibitors, for example, are metabolized by the same liver enzyme (CYP3A4) that breaks down statins, sedatives, and some heart medications. Take simvastatin with a boosted PI? Your risk of muscle damage skyrockets. Midazolam? Its levels can spike nearly 8-fold, leading to dangerous sedation.

Even common OTC drugs can cause trouble. St. John’s wort, often used for mild depression, speeds up the breakdown of many HIV drugs, dropping their levels below effective range. That’s why it’s absolutely contraindicated.

Newer drugs like doravirine are better in this regard. Only 12% of people on doravirine-based regimens needed dose adjustments for interactions, compared to 35% on efavirenz. That’s a big deal when you’re managing five or six other medications.

What’s New in Treatment: Long-Acting and Next-Gen Drugs

For many, daily pills are still the norm. But that’s changing.

Lenacapavir, approved in 2022 and now recommended by WHO for prevention, is an injectable that works for six months. Cabenuva, a monthly injection of cabotegravir and rilpivirine, has shown higher satisfaction rates than daily pills-94% of users in one trial preferred it. But there’s a catch: if you miss an injection, drug levels drop slowly over weeks. That’s a long window for resistance to develop.

Even more promising is VH-184, a new INSTI tested in early 2025. In a phase 2a trial, it reduced viral load by 1.8 log10 in people already resistant to dolutegravir and bictegravir. That’s huge. It’s not just another drug-it’s a lifeline for those with few options left.

And then there’s the islatravir implant, a once-a-year option that was put on hold in early 2025 due to unexpected drops in CD4 cells. It’s a reminder: even breakthroughs come with risks. The science is moving fast, but safety still comes first.

Testing, Monitoring, and Real-World Challenges

Resistance testing isn’t optional anymore. It’s mandatory at diagnosis-and again if treatment fails. In the U.S., 82% of newly diagnosed patients now get tested, up from 45% a decade ago. But in rural clinics, getting results can take three weeks. Meanwhile, the virus keeps replicating.

Genotype tests show which mutations are present. But interpreting them? That’s where expertise matters. A community provider might miss a subtle pattern. An infectious disease specialist sees the full picture. That’s why tools like the Stanford HIVdb algorithm and the NIH’s Drug Interaction Checker are critical. They’re not luxuries-they’re necessities.

And then there’s the human side. On Reddit, people share stories of switching from Atripla because insomnia kept them up all night. Others describe bone pain from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), leading them to switch to tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), which uses 90% less drug and spares kidneys and bones. One user on HIVPlusMag got HIV despite taking Truvada daily-genotype testing revealed the M184V mutation. That’s rare, but it happens.

Who’s at Risk-and What You Can Do

Resistance isn’t just a problem for people with long-term HIV. It’s also growing in people just starting treatment. In sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 30% of new infections involve drug-resistant strains. In the U.S., it’s about 17%. That’s why pre-screening matters. If you’re starting ART, you need a resistance test before the first pill.

And if you’re on ART? Adherence is everything. Set phone alarms. Use pill organizers. Link doses to daily habits-brushing teeth, eating breakfast. If you’re struggling, talk to your provider. There’s no shame in needing help. Switching to a once-daily, single-tablet regimen like Biktarvy or Dovato can make a world of difference.

For those on long-acting injections, schedule reminders. Don’t wait until the last minute. Missing one dose doesn’t mean failure-but missing two? That’s when the risk spikes.

Looking Ahead

The future of HIV treatment isn’t just about better drugs. It’s about smarter systems. AI tools like HIV-TRACE are already predicting transmission clusters with 87% accuracy by analyzing genetic sequences. That helps public health teams target interventions before outbreaks spread.

And the research doesn’t stop there. The NIH’s Martin Delaney Collaboratories are exploring CRISPR-based therapies that have cut viral DNA by 95% in animal models. A cure might still be years away-but the tools to manage HIV better than ever are here now.

For now, the message is clear: HIV is manageable. But it demands respect. Not just from patients, but from providers, systems, and policies. Because when resistance grows, it doesn’t just hurt one person. It threatens everyone.

Can you develop resistance to HIV meds if you take them perfectly?

It’s extremely rare if you take your meds exactly as prescribed and have no pre-existing resistance. Most resistance comes from missed doses, inconsistent timing, or stopping treatment. But even perfect adherence won’t prevent resistance if you start with a drug-resistant strain-so testing at diagnosis is critical.

Why do some HIV drugs need to be taken with food?

Some antiretrovirals, especially older protease inhibitors like ritonavir and lopinavir, need food to be absorbed properly. Without it, drug levels stay too low to work. Newer drugs like dolutegravir and bictegravir don’t require food-making them easier to fit into daily life.

Are generic HIV drugs as effective as brand names?

Yes, when they’re FDA-approved. Generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate costs about $60 a month compared to $2,800 for branded Truvada. The active ingredients are identical. The main difference is cost-not effectiveness. But switching from brand to generic in someone with prior resistance requires caution and testing.

What happens if you stop HIV meds and then restart later?

Stopping ART-even for a short time-can cause viral rebound and lead to new resistance mutations. If you restart, you might need a completely different regimen. Never stop without talking to your provider. Even if you feel fine, the virus is still there.

Can HIV resistance be passed to others?

Yes. Drug-resistant HIV can be transmitted just like wild-type HIV. About 17% of new HIV infections in the U.S. involve strains resistant to at least one drug. That’s why resistance testing is done at diagnosis-even for newly infected people.

How often should resistance testing be done?

At diagnosis, before starting treatment. Then again if the viral load becomes detectable after being suppressed. Routine testing every year isn’t needed if you’re doing well. But if treatment fails, testing is urgent.

Do HIV medications cause long-term side effects?

Yes, but they’re far less common than in the past. Older drugs like tenofovir disoproxil fumarate could cause kidney and bone loss. Newer versions like tenofovir alafenamide reduce those risks by 90%. Some people on protease inhibitors have higher heart disease risk, which is why statins like pitavastatin are now recommended for many. Regular monitoring catches these early.