Side Effect Risk Calculator

How This Tool Works

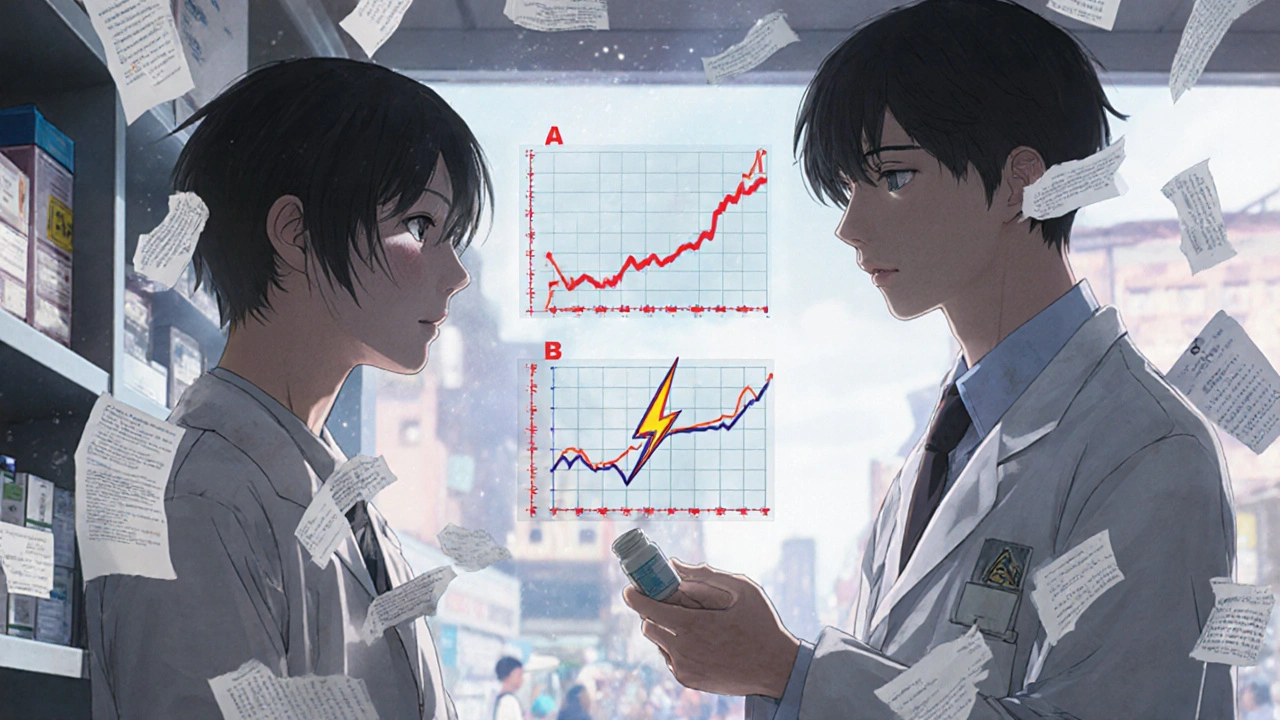

This tool helps you understand the relative likelihood of dose-related (Type A) versus non-dose-related (Type B) side effects based on your specific situation. Type A reactions are predictable and dose-proportional (70-80% of all side effects), while Type B reactions are unpredictable immune-driven reactions (15-20% of side effects but responsible for 70-80% of serious reactions).

Select a drug and complete the form to see your risk assessment.

When you take a medication, you expect it to help - not hurt. But side effects happen. Some are mild, like a headache or upset stomach. Others can land you in the hospital. The key to understanding why some side effects are predictable and others aren’t lies in a simple but powerful distinction: dose-related versus non-dose-related side effects.

What Are Dose-Related Side Effects?

Dose-related side effects - also called Type A reactions - are the most common. They make sense. If you take more of a drug, you get more of its effect. That includes the bad ones. These reactions are predictable, based on how the drug works in your body.Think of insulin. It lowers blood sugar. Too much? Your blood sugar drops dangerously low - hypoglycemia. That’s a classic dose-related reaction. Same with warfarin: too much thins your blood too much, leading to uncontrolled bleeding. Or digoxin, used for heart rhythm issues: even a small overdose can cause nausea, confusion, or dangerous heart rhythms.

These reactions follow the law of pharmacology: higher concentration at the target site = stronger effect. They’re not random. They’re tied to the drug’s known action. About 70-80% of all adverse drug reactions fall into this category. And they’re responsible for most hospital visits due to medications - especially in older adults. Anticoagulants, insulin, and blood pressure pills account for nearly two-thirds of emergency visits from side effects in people over 65.

What makes dose-related reactions especially risky? Narrow therapeutic windows. That means the gap between the right dose and the dangerous dose is tiny. For lithium, used for bipolar disorder, the safe range is 0.6 to 1.0 mmol/L. Go over 1.2 mmol/L? Toxicity kicks in - tremors, confusion, even seizures. For digoxin, toxicity starts just above 2.0 ng/mL, while the therapeutic level is 0.5-0.9 ng/mL.

Factors like kidney or liver problems make these reactions more likely. If your kidneys aren’t clearing the drug, it builds up. A drug interaction can do the same. For example, clarithromycin (an antibiotic) can slow down how your body breaks down statins. That spike in statin levels can cause severe muscle damage. Elderly patients are at higher risk too - their bodies process drugs slower, so even normal doses can become too much.

What Are Non-Dose-Related Side Effects?

Non-dose-related side effects - Type B reactions - are the scary ones. They’re unpredictable. They don’t follow the rules. You could take the exact same dose as someone else and have zero issues, while they develop a life-threatening rash or liver failure.These are immune-driven or idiosyncratic. Your body reacts as if the drug is a threat - even though it’s not. Anaphylaxis to penicillin is one example. You might have taken penicillin safely before. Then, on the next dose, your immune system goes haywire. Swelling, trouble breathing, drop in blood pressure - all within minutes. It doesn’t matter if you took 250 mg or 500 mg. The reaction happens once your immune system is primed.

Other examples: Stevens-Johnson syndrome from lamotrigine or sulfonamides - a blistering skin reaction that can destroy large areas of skin and mucous membranes. Or drug-induced liver injury from amoxicillin-clavulanate. These reactions can occur after the first dose, even if you’ve never had a problem before. That’s why they’re so hard to anticipate.

Only about 15-20% of all side effects are Type B. But they’re responsible for 70-80% of serious, life-threatening reactions and most drug withdrawals from the market. Their mortality rate is 5-10%, compared to less than 1% for dose-related reactions.

Why Do Non-Dose-Related Reactions Even Happen?

It seems odd. If all drugs work through chemistry, shouldn’t every effect depend on dose? The answer lies in individual biology.Researchers found four reasons why these reactions appear unrelated to dose:

- Methodological errors: Sometimes what looks like a non-dose reaction is just poor tracking - the dose wasn’t recorded right, or symptoms were misattributed.

- Hypersusceptibility: Some people reach the maximum reaction at very low doses. Their system is so sensitive that even a tiny amount triggers a full-blown response.

- Wide variation between people: Genetics, age, health status - all affect how a drug interacts with your body. One person’s safe dose is another’s trigger.

- Inaccurate dose measurement: Did you take the pill? Did it absorb properly? Did you miss a dose and then double up? Real-world dosing is messy.

But here’s the real kicker: many Type B reactions do have dose thresholds. They just vary wildly from person to person. For some, it’s 5 mg. For others, it’s 500 mg. In population studies, that looks random - hence the name “non-dose-related.” But individually, there’s often a line you can’t cross.

Genetics and Personalized Risk

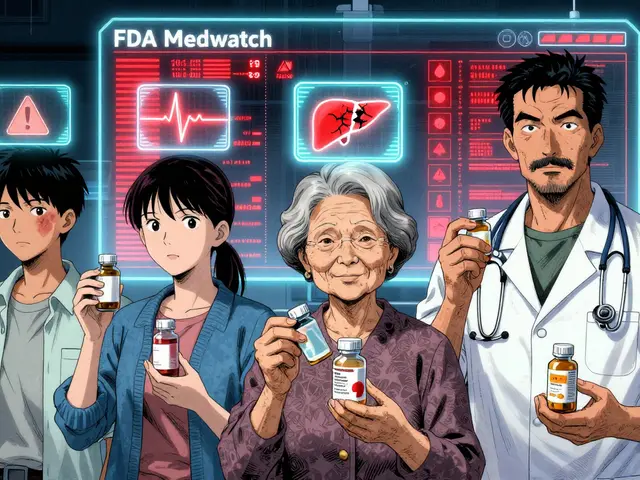

One of the biggest breakthroughs in understanding Type B reactions is genetics. Certain gene variants make you far more likely to have a severe reaction.Take abacavir, an HIV drug. People with the HLA-B*57:01 gene variant have a 53% chance of developing a life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction. Those without it? Less than 0.1% risk. Testing for this gene before prescribing abacavir is now standard. It costs $150-300 - far cheaper than treating a reaction.

Same with carbamazepine, used for seizures and nerve pain. In people of Asian descent, the HLA-B*15:02 allele strongly links to Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Testing is recommended before starting the drug. In the U.S., the FDA now requires genetic testing for 28 drugs - including abacavir, carbamazepine, and allopurinol - to prevent these reactions.

These aren’t just lab findings. They’re changing how drugs are prescribed. Pharmacogenomics - using your genes to guide medication choices - is growing fast. The global market is expected to hit nearly $18 billion by 2030. The FDA includes pharmacogenomic info in over 300 drug labels. Hospitals are starting to screen high-risk patients before giving certain drugs.

How Doctors Manage Each Type

Knowing the difference changes everything.For dose-related reactions, the fix is usually simple: adjust the dose. Monitor blood levels. For drugs like vancomycin, digoxin, or phenytoin, doctors check blood concentrations regularly to stay in the safe range. If kidney function drops, they lower the dose. If another drug interferes, they switch or reduce.

For non-dose-related reactions, the rule is clear: stop the drug - permanently. No second chances. Even a tiny dose after a prior reaction can trigger it again. You’ll need to avoid not just that drug, but often similar ones in the same class.

Prevention is key. For penicillin allergies, skin testing can help determine if you’re truly allergic - many people outgrow it or were misdiagnosed. Graded challenge tests (giving small, increasing doses under supervision) can safely confirm safety in low-risk cases.

And for drugs with known high-risk reactions, systems are in place. The FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) require special training, monitoring, or restricted distribution for drugs with serious Type B risks. As of 2022, over 70 drugs had active REMS programs.

Real-World Impact

Clinicians see the difference every day.A doctor in Halifax recently had two patients on warfarin. One developed a dangerously high INR (8.2) after starting amiodarone - a classic drug interaction. Dose adjustment and close monitoring fixed it. Type A.

The other patient developed Stevens-Johnson syndrome after her first dose of lamotrigine - even though she followed the titration schedule exactly. No warning. No way to predict. Type B. She spent weeks in the hospital. Her skin peeled off. She’ll never take that drug again.

Patients feel it too. One person on Inspire.com wrote: “I broke out in a rash after one 500mg dose of amoxicillin. My doctor said it wasn’t about the dose - it was my immune system. Now I carry an epinephrine pen everywhere.”

Cost-wise, Type A reactions drive most medication-related expenses - around $130 billion a year in the U.S. But Type B reactions drive lawsuits. When a drug causes a rare but deadly reaction, the legal fallout is massive. That’s why pharmaceutical companies invest heavily in genetic screening and risk mitigation.

What’s Next?

The future of safe prescribing is personal. Machine learning models are getting better at predicting dose-related reactions - accuracy is around 82%. But for Type B? Only 63%. That gap shows how much we still don’t understand.But progress is real. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) now provides clear guidelines for dosing based on genetics for over 50 gene-drug pairs. The FDA is moving toward approving software that helps doctors calculate individualized doses using genetic, age, weight, and lab data.

For patients, this means more testing before prescriptions. For doctors, it means fewer surprises. And for everyone, it means safer medicine - not because we’re taking less, but because we’re taking the right dose, for the right person.

Are all side effects dose-related?

No. About 70-80% of side effects are dose-related (Type A), meaning they get worse as the dose increases. The other 15-20% are non-dose-related (Type B), like allergic reactions or rare genetic responses. These can happen at any dose, even a very low one, and are often unpredictable.

Can a non-dose-related reaction happen on the first dose?

Yes. While some Type B reactions require prior exposure to trigger sensitization (like penicillin allergies), others - such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome from lamotrigine - can occur on the very first dose. That’s why these reactions are so dangerous: there’s no warning.

Is it possible to predict non-dose-related side effects?

Sometimes. For certain drugs, genetic testing can identify high-risk patients. For example, testing for the HLA-B*57:01 gene before giving abacavir prevents life-threatening reactions in nearly all cases. Skin tests can help confirm penicillin allergies. But for many Type B reactions, prediction is still unreliable - which is why they remain a major challenge in pharmacology.

Why do some people have severe reactions to low doses?

Some people are hypersusceptible - their bodies react strongly even to tiny amounts of a drug. This is often due to genetics, liver or kidney function, or immune system quirks. What’s a safe dose for most people might be a trigger for them. That’s why one-size-fits-all dosing doesn’t always work.

Which type of side effect is more dangerous?

Dose-related reactions are more common, but non-dose-related reactions are far more dangerous. While Type A reactions have a mortality rate under 1%, Type B reactions can be fatal in 5-10% of cases. They’re also the main reason drugs get pulled from the market or carry black box warnings.

Can I avoid dose-related side effects by taking less?

Not always. Many drugs need to be taken at a specific dose to work. Taking less might mean the drug doesn’t help - and you could get worse. The goal isn’t to take less, but to take the right amount for you. That’s why monitoring blood levels, checking kidney function, and watching for drug interactions matters more than just lowering the dose.

Comments (10)

Koltin Hammer

It’s wild how much we still don’t know about why some people react like their body’s on fire from a single pill while others take ten times the dose and feel fine. It’s not just biology-it’s like our DNA holds secret codes we’re only just cracking. I’ve seen friends on carbamazepine get rashes, others on it for decades with zero issues. The HLA-B*15:02 testing? That’s not science fiction anymore. It’s saving lives. And yet, most doctors still don’t screen unless it’s mandatory. We’re treating medicine like it’s a one-size-fits-all toaster when it’s actually a custom-tailored suit.

Pharmacogenomics isn’t the future. It’s already here. The question is whether our healthcare system has the guts to catch up.

Jessica M

The distinction between Type A and Type B adverse reactions is foundational to clinical pharmacology. Type A reactions, being pharmacologically predictable, are amenable to dose titration, therapeutic drug monitoring, and pharmacokinetic adjustments. Conversely, Type B reactions, being idiosyncratic and immune-mediated, necessitate immediate discontinuation and avoidance of cross-reactive agents. The integration of pharmacogenomic screening into pre-prescription protocols represents a paradigm shift toward precision medicine, significantly reducing morbidity and mortality associated with preventable hypersensitivity reactions.

Victoria Short

So basically, if you get a rash from penicillin, you’re just unlucky? Cool. I’ll just keep taking meds and hoping my body doesn’t decide to revolt.

Connor Moizer

Stop acting like this is some deep mystery. Of course some people react badly-it’s called being a walking allergy machine. The real problem? Doctors still prescribe like it’s 1995. No blood tests. No genetics. Just ‘here’s a pill, go.’ If you’re over 50, on more than three meds, or have a kidney issue? You’re basically playing Russian roulette with your liver. Stop blaming the drug. Start blaming the system.

Eric Gregorich

Think about it: we live in a world where we can map a galaxy 13 billion light-years away, but we still can’t predict if a 500mg pill will turn your skin into a melted candle. It’s not just science-it’s existential. Why does my body see this drug as an enemy? Why does yours not? Is it fate? Genetics? Some cosmic glitch in the human operating system? We call it ‘idiosyncratic’ like that explains anything. It doesn’t. It just means we’re scared to admit we don’t understand the most basic thing about our own biology: how we react to chemicals we invented. And until we stop pretending we’re in control, we’re just guessing in the dark.

Parv Trivedi

This is such an important topic. In India, many people take antibiotics without prescriptions, and side effects are often ignored. But learning that some reactions are genetic and not about dose gives us hope. If we can test before giving drugs like carbamazepine, we can save so many lives. I hope more countries adopt these practices soon. Medicine should be personal, not random.

Phil Best

Oh wow, so the drug company’s $10 billion drug? Yeah, it kills 1 in 10,000 people. But hey-it’s ‘non-dose-related,’ so it’s not their fault, right? Just bad luck for the unlucky few. Meanwhile, the FDA approves it, doctors prescribe it, and we all just shrug and say ‘well, that’s medicine.’

Let’s be real: Type B reactions are the reason we have black box warnings. And also the reason we have lawsuits that make CEOs cry. It’s not science-it’s a liability lottery.

Erika Lukacs

Is the distinction between dose-related and non-dose-related not itself a construct of our need to impose order on chaos? Perhaps all reactions are dose-related, but the ‘dose’ is not merely milligrams-it is the cumulative weight of trauma, environment, epigenetics, and cultural context. The pill is the same, but the person is not. We measure in micrograms, yet ignore the megagrams of lived experience that shape biology.

Rebekah Kryger

Let’s be honest-Type B reactions are just pharmacology’s way of saying ‘we have no idea.’ They call it ‘idiosyncratic’ like it’s a technical term, but it’s just code for ‘we can’t explain it, so we’re gonna label it and move on.’ And don’t even get me started on ‘hypersusceptibility.’ That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘your body is broken in a way we can’t fix.’

Meanwhile, we’re spending billions on genetic tests for 28 drugs while ignoring that 80% of reactions are still Type A-and those are the ones we could actually prevent with basic monitoring. We’re optimizing the rare and ignoring the common. Classic.

Willie Randle

For anyone reading this and thinking, ‘I’m not the kind of person who gets weird drug reactions’-you’re wrong. You might be now. Or you might be next. The point isn’t to scare you. It’s to empower you. Ask your doctor: ‘Is there a genetic test for this?’ ‘Has my kidney function been checked?’ ‘Could this interact with my other meds?’ You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to care enough to ask. That’s how you protect yourself. And that’s how we make medicine better-for everyone.