The U.S. healthcare system runs on generics. Around 9 out of 10 prescriptions filled today are for generic drugs. But how do these low-cost versions of brand-name medicines get approved? It’s not magic. It’s a carefully designed legal and scientific process built on one law: the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984.

The Legal Foundation: Hatch-Waxman and the ANDA Pathway

Before 1984, generic drug makers had to repeat every single clinical trial done by the original drug company. That meant spending hundreds of millions and waiting years-just to sell the same chemical. It wasn’t practical. So Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This law created the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA.The word “abbreviated” is key. Generic manufacturers don’t need to prove safety or effectiveness from scratch. Instead, they rely on the FDA’s prior approval of the brand-name drug, called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The ANDA lets them skip animal studies and large human trials. All they need to show is that their version works the same way in the body.

The Office of Generic Drugs (OGD), part of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, runs this whole system. In 2023 alone, they approved 90 new generic drugs. That’s not a small number-it’s the backbone of affordable care.

What the FDA Actually Requires

Getting approved isn’t easy, even with the abbreviated process. The FDA has strict rules. A generic drug must:- Contain the exact same active ingredient as the brand drug

- Match the brand in strength, dosage form (pill, injection, cream, etc.), and how it’s taken (by mouth, injection, etc.)

- Have the same medical uses and labeling

- Be bioequivalent

- Meet the same quality standards for identity, strength, purity, and stability

- Be made in a facility that passes the same inspections as brand-name plants

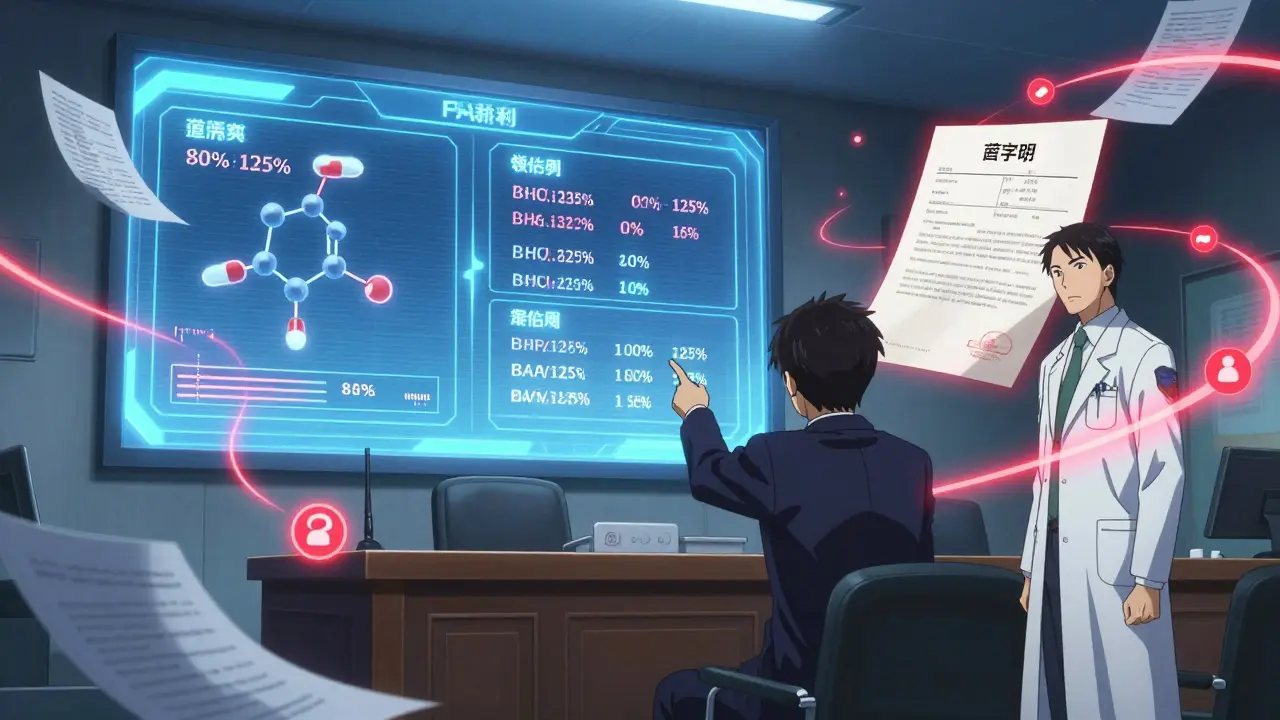

The most critical part? Bioequivalence. This means the generic must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. The FDA tests this using pharmacokinetic studies in 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Blood samples are taken over time to measure absorption. If the generic’s levels fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s, it’s approved.

Don’t be fooled by inactive ingredients. Fillers, dyes, and preservatives can be different. But they can’t affect how the drug works. The FDA checks these too-just not as intensely as the active part.

The Approval Timeline and GDUFA

The Hatch-Waxman Act originally said the FDA had 180 days to review an ANDA. That didn’t work. Backlogs grew. So in 2012, Congress created the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). This lets the FDA collect fees from generic companies to hire more reviewers and set clear timelines.Today, under GDUFA III (effective through 2027), the FDA commits to:

- Review standard ANDAs within 10 months

- Review priority ANDAs-like first generics or drugs in shortage-within 8 months

These aren’t suggestions. They’re performance goals. If the FDA misses them, they have to pay the company back. That’s how they stay accountable.

Before a full review even starts, the FDA does a filing review. If the application is missing key data-like bioequivalence results or facility info-they send a Refuse-to-Receive letter. No review. No refund. You have to fix it and pay again.

Patents, Exclusivity, and Legal Hurdles

One of the trickiest parts of getting a generic approved isn’t science-it’s law. Brand-name companies hold patents. The Hatch-Waxman Act lets generic makers challenge them.When submitting an ANDA, the applicant must certify one of four things about the brand’s patents. The most aggressive is a Paragraph IV certification: “We believe this patent is invalid or won’t be infringed.” That’s a legal shot across the bow.

If the brand company sues, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months. That’s called a “30-month stay.” It’s a major delay tactic. Some companies use it to protect profits, even if the patent is weak. The FDA can’t override it.

There’s also exclusivity. If a brand company gets 180-day exclusivity for being the first to file a Paragraph IV certification, no other generic can enter the market during that time-even if their application is approved. This creates a race to the FDA door.

Complex Generics: Where the System Gets Stuck

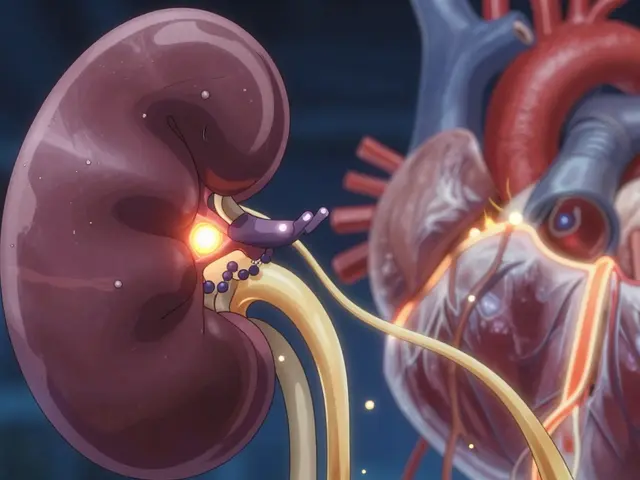

The ANDA process works great for simple pills. But what about inhalers, complex creams, or extended-release tablets? These aren’t easy to copy. The active ingredient might be the same, but how it’s delivered matters.For example, a generic inhaler must match the brand’s particle size, spray pattern, and lung deposition. That’s not something you can prove with a blood test. It requires specialized testing, sometimes even clinical studies.

The FDA admits this is a growing problem. That’s why they launched the Complex Generic Drug Product Development Resources initiative. They’re working with manufacturers to build better testing standards. But progress is slow. Many complex generics still take years to get approved.

Who Makes These Drugs and Why It Matters

The U.S. generic market is worth about $125 billion. Major players include Teva, Sandoz, Viatris, and Amneal. But there are hundreds of smaller companies too, especially those focusing on hard-to-make products.Here’s the catch: most active ingredients are made overseas. Over 80% of the raw materials for generics come from India and China. The FDA inspects these facilities, but supply chain risks remain.

In October 2025, the FDA announced a new pilot program to speed up reviews for companies that manufacture and test their generics in the U.S. It’s a signal: they want more domestic production. Less reliance on foreign suppliers. More control over quality.

Why This System Works-And Why It’s Essential

Generic drugs cost 80% to 85% less than brand-name versions. That’s not a small savings. It’s life-changing for people on fixed incomes, those without insurance, or managing chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure.The FDA says increasing generic availability helps “make treatment more affordable and increases access to healthcare for more patients.” That’s not just a slogan. It’s a measurable outcome. In 2023, the approval of the first generic version of Vivitrol-a treatment for opioid addiction-was called “of prime importance” given the ongoing crisis.

Experts call the ANDA pathway “the most significant provision for the generic industry.” Without it, low-cost drugs wouldn’t exist at scale. The system isn’t perfect. Patent thickets, complex products, and foreign supply chains are real challenges. But it works. And it saves billions every year.

What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

The future isn’t just about more pills. It’s about better science. The FDA is investing in tools to evaluate complex generics. They’re pushing for more U.S. manufacturing. And they’re watching biosimilars-the biologic version of generics-closely.Biosimilars aren’t covered by the ANDA pathway. They fall under a different law: the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. But the goal is the same: bring down prices and increase access.

For now, the ANDA system remains the engine of affordable medicine. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t make headlines. But every time someone fills a prescription for a $4 generic instead of a $400 brand, it’s because of this process.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires that generic drugs meet the same strict standards for safety, strength, quality, and performance as brand-name drugs. They use the same active ingredients and are made in FDA-inspected facilities. The only differences are in inactive ingredients like dyes or fillers, which don’t affect how the drug works.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved?

Under current FDA rules, standard ANDA applications are reviewed within 10 months. Priority applications, such as first generics or drugs in shortage, are reviewed within 8 months. This timeline is enforced through the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), which set clear performance goals.

Why do some generic drugs take longer to come to market?

Patent disputes are the biggest delay. If the brand-name company sues for patent infringement, the FDA must wait 30 months before approving the generic, even if the application is otherwise complete. Complex drugs-like inhalers or long-acting injections-also take longer because they require more advanced testing beyond standard bioequivalence studies.

Can a generic drug be different from the brand in any way?

Yes, but only in non-active ingredients. Generics can have different colors, shapes, flavors, or preservatives. They can’t change the active ingredient, strength, dosage form, or how it’s absorbed by the body. The FDA ensures these differences don’t affect safety or effectiveness.

Is the FDA’s approval of generics reliable?

Yes. The FDA reviews every ANDA for scientific rigor and manufacturing quality. They inspect all production sites-domestic and foreign-using the same standards as for brand-name drugs. In 2023, over 90% of first-cycle ANDA submissions met approval requirements, showing a mature and reliable system.

Comments (2)

Harriot Rockey

Love that generics are saving lives and wallets 🙌 Seriously, my grandma takes 5 meds a day and 4 of them are generic-she pays $4 a month for everything. This system? Pure genius.

Joy Johnston

The ANDA pathway represents one of the most meticulously engineered public health interventions in modern pharmaceutical policy. The bioequivalence thresholds of 80–125% are not arbitrary-they are grounded in pharmacokinetic statistical models validated across decades of clinical data. The FDA’s adherence to GDUFA timelines reflects institutional accountability rarely seen in regulatory bodies.