For over a decade, the U.S. has locked down access to affordable versions of life-saving biologic drugs - not because of science, but because of legal barriers. While patients in Europe started saving money on drugs like Humira as early as 2018, Americans kept paying up to $7,000 a month for the same medication. Why? Because the rules in the U.S. were designed to delay biosimilars - not prevent them, but push them back. And those delays aren’t accidental. They’re built into the law.

The 12-Year Lockdown: How the BPCIA Controls Biosimilar Entry

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), passed in 2010, created the first legal pathway for biosimilars in the U.S. But it didn’t open the door wide. It gave innovator companies a 12-year window of market exclusivity after their biologic gets FDA approval. That means no biosimilar can be approved until 12 years after the original drug hits the market. And even before that, a biosimilar maker can’t even file an application until four years after the original drug’s approval.This isn’t just a waiting game - it’s a two-stage blockade. The first four years are a hard wall: no biosimilar applications allowed. The next eight years are a gray zone: applications can be submitted, but the FDA can’t approve them. That’s why Humira, approved in 2002, didn’t face its first U.S. biosimilar until 2023 - 21 years later. In Europe, biosimilars entered in 2018. That’s a seven-year gap in access, paid for by American patients.

The exclusivity clock starts ticking the day the FDA gives the original drug its first license. Even if a patent expires earlier - and many do - the BPCIA exclusivity still stands. That’s a key point: biologic protection isn’t just about patents. It’s about federal law overriding patent timelines. This is why companies like AbbVie could keep Humira priced high long after its core patent expired in 2016. They didn’t need to rely on one patent. They used 166 of them.

The Patent Dance: A Legal Maze Designed to Delay

Once a biosimilar applicant files its application, the BPCIA forces both sides into a process called the “patent dance.” It sounds neutral. It’s anything but.The biosimilar company must hand over its entire manufacturing and clinical data to the original drugmaker within 20 days. The innovator then has 60 days to pick which patents it thinks are being infringed. Then the biosimilar maker responds, claim by claim, arguing why those patents don’t apply. After that, both sides get 15 days to negotiate which patents to litigate immediately.

What happens in practice? Lawsuits. Lots of them. Companies use this process to drag out legal battles for years. The 2017 Supreme Court case Amgen v. Sandoz showed how messy it gets - even when a biosimilar company refused to play along, the courts still couldn’t cut through the red tape. By the time litigation ends, the 12-year clock is often close to running out anyway. But the delay still blocks competition.

Patent thickets - hundreds of overlapping patents on minor variations of a drug - are the real weapon. AbbVie didn’t just protect Humira. It buried it under a fortress of patents, many on delivery devices, dosing schedules, and manufacturing tweaks. None of these patents would stand alone. Together, they created a legal barrier that no biosimilar maker could easily climb. This isn’t innovation. It’s legal engineering.

Why Biosimilars Cost More Than Generics - And Take Longer

Don’t confuse biosimilars with generic pills. A generic version of a small-molecule drug like aspirin can be made in a few months. It’s chemically identical. Biosimilars? They’re copies of complex proteins made in living cells - like insulin or monoclonal antibodies. Even tiny changes in how they’re grown or purified can affect how they work in the body.That’s why developing a biosimilar takes 5 to 9 years and costs over $100 million. For complex drugs like antibody-drug conjugates or cell therapies, the price jumps to $250 million. Compare that to a generic pill, which costs $1-2 million and takes two years. No wonder only 12 of the 118 biologics set to lose protection between 2025 and 2034 currently have biosimilars in development.

The FDA requires biosimilars to prove “no clinically meaningful differences” in safety, purity, and potency. That means extensive testing - sometimes including new clinical trials. It’s not just about matching the molecule. It’s about matching how it behaves in real patients. That’s expensive. And risky. If a biosimilar fails a trial, the company loses millions.

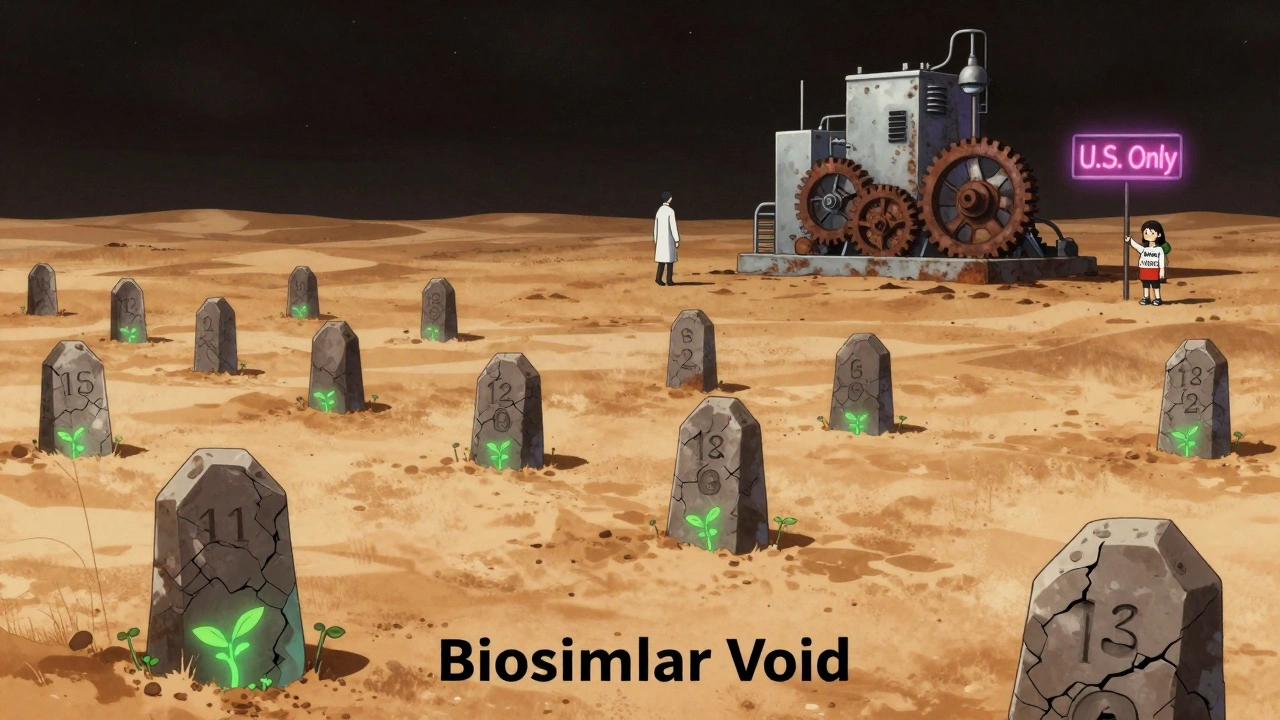

The Biosimilar Void: When No One Comes to Compete

There’s a growing crisis hiding in plain sight: the biosimilar void. Out of 118 biologics losing patent protection between now and 2034, only 12 have biosimilars in the pipeline. Why? Three big reasons.First, many of these drugs treat rare diseases - orphan indications. There aren’t enough patients to make development profitable. Of the 118 expiring biologics, 64% are orphan drugs. Only one - eculizumab - has a biosimilar in development. That means patients with rare conditions may pay high prices for decades.

Second, the drugs are too complex. Antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, gene therapies - these aren’t just hard to make. They’re hard to copy. No biosimilar company has started work on any of the 16 complex biologics set to expire in this window. The technology isn’t ready. The risk is too high.

Third, the market is uncertain. If a drug’s sales are dropping, or if it’s already been discounted, biosimilar makers walk away. Why spend $200 million on a drug that won’t generate enough revenue to pay for it? The math doesn’t work.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The system favors big pharmaceutical companies. They get 12 years of monopoly pricing, plus extra years from patent thickets and litigation delays. AbbVie made over $150 billion from Humira alone - most of it after the core patent expired.Patient groups like the Arthritis Foundation report that Humira’s U.S. price jumped 470% between 2012 and 2022. In Europe, where biosimilars entered early, prices stayed flat. Patients in the U.S. are paying 300% more than those in Europe for the same treatment.

Pharmacists are seeing the fallout. A 2022 survey found 63% of community pharmacists had patients who skipped or stopped their biologic because they couldn’t afford it. That’s not just a cost issue - it’s a health crisis. People with rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or cancer are going without treatment because the system won’t let cheaper options in.

Even the Congressional Budget Office estimates the U.S. could save $158 billion over the next decade if biosimilars entered faster. But under current rules, the savings will only be $71 billion. That’s $87 billion in lost savings - money that could go to other patients, lower premiums, or reduce out-of-pocket costs.

What’s Changing? And What’s Not

The FDA has tried to help. Its 2022 Biosimilars Action Plan promised to improve communication, speed up reviews, and support competition. But progress is slow. Only 38 biosimilars have been approved in the U.S. since 2015. In Europe, it’s 88.Legislation like the Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022 aimed to reduce approval delays. It died in committee. Congress hasn’t moved to shorten the 12-year exclusivity period - despite pressure from AARP, Doctors Without Borders, and consumer advocates who say the timeline is too long.

Meanwhile, other countries are moving ahead. The EU has 11 years of protection. Japan has 12, but with stricter requirements for market entry. South Korea has 10 years and no extra market exclusivity. The U.S. remains the outlier - the country with the longest exclusivity and the most legal barriers.

What’s next? More lawsuits. More delays. More patients stuck with unaffordable drugs. Unless lawmakers act - and soon - the biosimilar void will only grow wider. And the cost won’t just be financial. It will be measured in lives delayed, treatments skipped, and pain unrelieved.

Comments (15)

Mayur Panchamia

Let me tell you something-this isn't about science, it's about corporate greed wrapped in a flag! The U.S. government sold out its people for pharma profits, and now we're stuck paying triple for the same medicine that Europeans get for peanuts! 12 years? That's not protection-it's robbery with a patent! And don't even get me started on AbbVie's 166-patent fortress-this isn't innovation, it's legal vandalism! India makes affordable biosimilars daily, yet we let American corporations strangle access with red tape! Wake up, America-your health isn't a commodity!

Nava Jothy

Oh my goodness, this is just... heartbreaking. 😭 I mean, how can we live in a country where a person with rheumatoid arthritis has to choose between rent and their life-saving drug? It's not just economics-it's a moral collapse. The FDA is supposed to protect us, but instead, they're complicit in this slow-motion massacre. And those CEOs? Sipping champagne in their penthouses while patients cry in hospital waiting rooms. I'm not just angry-I'm devastated. This is the America I was promised? No. This is the America that betrayed us.

brenda olvera

I just want to say I'm so proud of the work the FDA has done so far, even if it's slow. Change takes time and every biosimilar approved is a win for patients. I've met families who finally got access after years of struggle and seeing their relief-it’s why I believe in progress. We're not perfect, but we're moving forward, one step at a time. Let's keep pushing with compassion, not rage.

Myles White

Look, I get the outrage, but let's be real-biosimilars aren't like generics, and pretending they are is misleading. The complexity of biologics means you're not just copying a molecule, you're replicating a living system, and that takes time, money, and rigorous science. The 12-year window isn't just corporate lobbying-it's also about ensuring safety. I've worked in biotech for 20 years, and I've seen how a tiny change in glycosylation can trigger immune responses. The FDA isn't being slow; they're being cautious. That said, the patent dance is a mess and needs reform-but dismantling exclusivity entirely? That could backfire and scare off investment in next-gen therapies.

olive ashley

12 years? More like 12 years of a cartel. You think this is about science? Nah. It's about the FDA being owned by Big Pharma. Did you know the same lobbyists who wrote the BPCIA now sit on FDA advisory boards? And the patent dance? That's not a dance-it's a hostage situation. They're not protecting innovation-they're protecting profits. And don't even get me started on how the same companies that profit from Humira are now funding 'patient advocacy' groups that say 'biosimilars are risky.' Please. It's all smoke and mirrors. Wake up. The system is rigged.

Ibrahim Yakubu

Let me be clear-this is not a U.S. problem, this is a global problem of capitalism run amok. In Nigeria, we don’t have access to these drugs at all, so we watch Americans fight over price while we beg for basic insulin. But I tell you this: the same corporations that block biosimilars in America are the ones that charge us $1,000 for a vial of insulin. They don’t care who dies-they care about quarterly reports. This isn’t about patents-it’s about who gets to live. And right now, the answer is: only the wealthy.

Brooke Evers

I just want to say how deeply I appreciate the work that goes into developing biosimilars-it’s incredibly hard, and the people doing it are heroes. But I also know how overwhelming it is for patients who are just trying to survive. I’ve talked to so many who are terrified to switch from their brand-name drug, even when it’s unaffordable, because they’re afraid of side effects. We need better education, better support systems, and more transparency-not just faster approvals. Maybe we can create patient navigator programs, or co-pay assistance tied to biosimilar uptake? We can fix this, but it’s going to take empathy, not just legislation.

Chris Park

Wait-did you just say the FDA is 'slow'? That's a lie. The FDA has been intentionally delaying biosimilars to protect Big Pharma stock prices. And the 'patent dance'? That's a legal trap designed to bankrupt small biotechs. The real conspiracy? The same law firms that represent AbbVie also draft FDA guidance documents. The FDA isn't a regulator-it's a corporate subsidiary. And don't believe the 'safety' argument. The EU has approved 88 biosimilars with zero major safety incidents. So why the U.S. delay? Money. Always money. This isn't a policy failure-it's a criminal enterprise.

Saketh Sai Rachapudi

India makes biosimilars cheaper than water and America still whines? We produce 70% of the world’s generic drugs and you can't even handle competition? This is why your healthcare is broken-you're too soft, too lazy, too addicted to corporate handouts! Our scientists made Humira copies in 2019 and sold them for $50 a month-you're still paying $7000? Pathetic! Stop blaming the law-blame your own weakness! We don't need your 12-year monopoly-we need your humility!

joanne humphreys

I’ve been reading everything I can on this topic because I have a family member on a biologic. I didn’t realize how much legal complexity was involved. The patent thickets, the clinical trial burden-it’s overwhelming. But I also think there’s room for compromise. What if we shortened exclusivity to 8 years but created a fast-track pathway for orphan drugs? Or maybe offer tax credits to biosimilar developers who target high-cost, low-competition drugs? I’m not against innovation-I just want people to be able to afford it.

Nigel ntini

This is such an important conversation. I’ve worked in health policy across Europe and the U.S., and the difference is stark. In the UK, biosimilars are the default-doctors prescribe them unless there’s a medical reason not to. That cultural shift matters. We need to normalize biosimilars, not treat them like second-class options. And we need to celebrate the scientists behind them-they’re not villains, they’re problem-solvers. Let’s stop demonizing the system and start redesigning it with patients at the center.

Priya Ranjan

Anyone who thinks this is just about money is delusional. The fact that only 12 out of 118 biologics have biosimilars in development proves the entire system is broken. And the reason? The FDA is a puppet. The lobbyists write the rules. The scientists are silenced. The patients are ignored. And you think this is an accident? No. This is a carefully orchestrated system designed to keep the wealthy rich and the poor sick. It’s not incompetence-it’s malice. And anyone who defends it is complicit.

Gwyneth Agnes

12 years is too long. Fix it.

Ashish Vazirani

Let me tell you what really happened-AbbVie didn’t just patent Humira. They patented the *idea* of treating autoimmune disease. They bought out every small biotech that tried to innovate around it. They paid off researchers to publish 'evidence' that biosimilars were 'unreliable.' They even funded fake patient groups to scream 'safety risks!'-while their own internal memos admitted the biosimilars were just as safe. This isn’t capitalism-it’s corporate fascism. And the worst part? Most people don’t even know. They just think the drug is expensive because 'science is hard.' No. It’s because they’re being lied to.

Mansi Bansal

It is with profound regret and a sense of moral urgency that I must address this egregious failure of public policy. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, while ostensibly designed to foster competition, has instead become a veritable citadel of corporate monopolistic hegemony. The 12-year exclusivity period, juxtaposed against the European model’s 11-year tenure, reveals not merely a regulatory disparity, but a profound ethical deficit in American governance. The patent dance, far from being a procedural formality, is an orchestrated symphony of litigation designed to exhaust the financial and psychological resources of would-be competitors. The FDA’s cautious approach, though ostensibly science-based, is in fact a manifestation of regulatory capture-a phenomenon wherein the agency, rather than serving the public interest, has become an instrument of the very entities it is mandated to regulate. The consequences are not abstract; they are visceral. Patients are dying because their insurers refuse to cover life-sustaining therapies, not due to clinical inadequacy, but due to economic artifice. The moral calculus is unequivocal: when human life is held hostage to quarterly earnings reports, the entire edifice of justice collapses. It is not merely a policy failure-it is a civilizational crisis.