Frailty and Polypharmacy Risk Assessment

Answer questions based on the person's current medications and health status. This tool helps identify potential risks from polypharmacy based on clinical criteria from the American Geriatrics Society.

- Number of medications: Count all prescription, OTC, and supplement medications

- Frailty signs: Check all that apply (5 signs total)

- High-risk meds: Check any medications from the Beers Criteria list

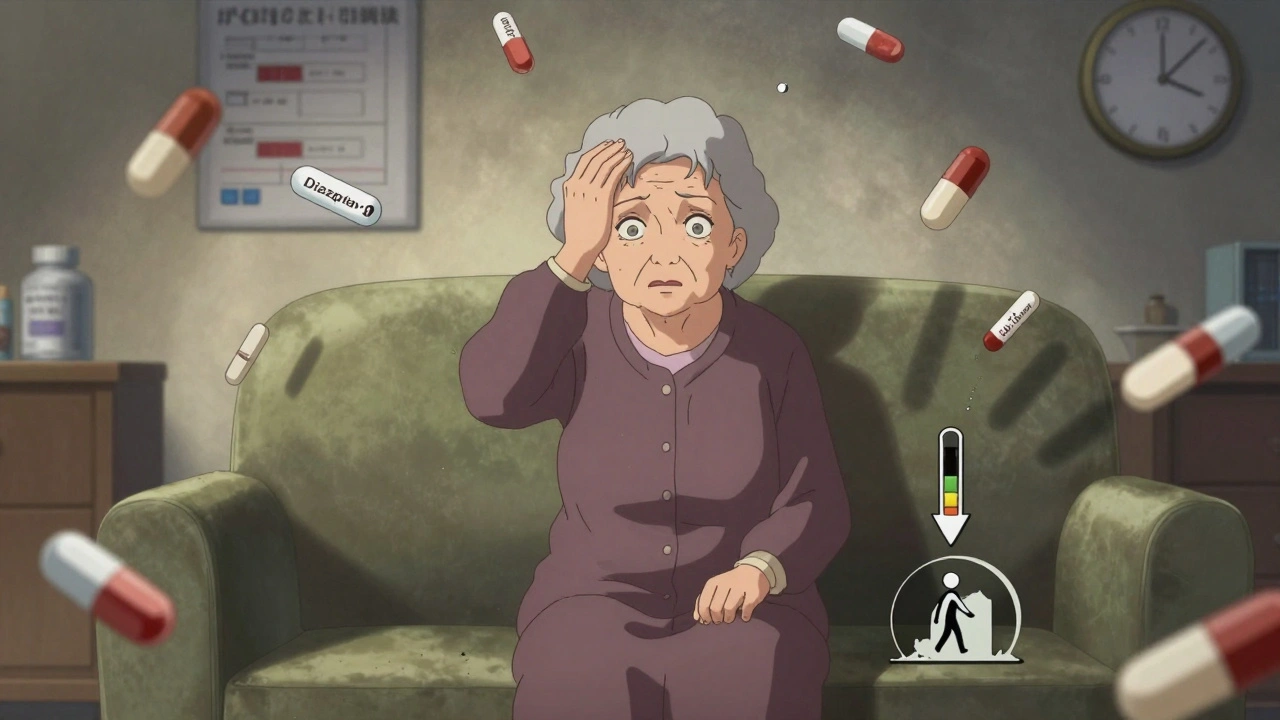

When an older adult is taking five, ten, or even fifteen medications a day, it’s not just about managing diseases-it’s about surviving a storm of side effects. Frailty and polypharmacy don’t just coexist; they feed each other. One makes the other worse. And the result? Dizziness that leads to falls. Constipation that turns into hospital visits. Confusion that gets mistaken for dementia. This isn’t rare. It’s routine in too many homes and nursing facilities across North America.

What Frailty Really Means in Older Adults

Frailty isn’t just being old or weak. It’s a clinical condition defined by five specific signs: unintentional weight loss, feeling exhausted most days, weak grip strength, slow walking speed, and low physical activity. If someone has three or more of these, they’re classified as frail. One or two? They’re prefrail-on the edge. And here’s the catch: nearly 75% of older adults taking five or more medications fall into one of those two categories. It’s not just about feeling tired. Frailty means your body has less reserve. A minor infection, a change in meds, even a bad night’s sleep can send you into a downward spiral. And the more pills you take, the more your body struggles to cope.Polypharmacy: When More Medicines Mean More Problems

Polypharmacy means five or more daily medications. Hyper-polypharmacy? Ten or more. In the U.S., nearly half of older adults now fall into this category. For those with heart disease or diabetes, it’s even higher-over 60%. But here’s what most people don’t realize: it’s not the number of diseases that causes this. It’s the system. Each specialist sees one problem. Cardiologist? Add a blood thinner. Endocrinologist? Add another diabetes pill. Neurologist? Add something for tremors. No one is looking at the whole picture. And every new drug adds risk. A 2023 study found that for every extra medication an older adult takes, their chance of becoming frail goes up by 12%. That’s not a small risk. That’s a ticking clock.The Vicious Cycle: How Frailty and Polypharmacy Feed Each Other

This isn’t a one-way street. Frailty makes you more likely to be prescribed more drugs. And more drugs make you frailer. It’s a loop. Take dizziness, for example. A medication for high blood pressure causes lightheadedness. The person stumbles once, then again. They get labeled as "unsteady." A physical therapist is called. Then a fall risk assessment. Then a balance medication. Then a sleep aid because the balance drug keeps them awake. Then a laxative because the sleep aid causes constipation. Suddenly, they’re on eight meds. Their grip weakens. They walk slower. They stop going outside. They become frail. And it works the other way too. Frail people are more sensitive to drugs. Their kidneys don’t filter as well. Their liver slows down. A dose that’s safe for a 50-year-old can be toxic for a frail 80-year-old. Even a small change in medication can trigger confusion, falls, or hospitalization.What Medications Are Most Dangerous for Frail Older Adults?

Not all pills are created equal. Some are far more likely to cause harm. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists the worst offenders:- Benzodiazepines (like diazepam or lorazepam) for sleep or anxiety-high risk of falls and confusion.

- Anticholinergics (like diphenhydramine or oxybutynin)-linked to memory loss, constipation, urinary retention.

- NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or naproxen)-can cause kidney damage, stomach bleeding, and worsen heart failure.

- First-generation antihistamines-often found in OTC sleep aids and cold meds, they slow brain function.

- Long-acting sulfonylureas (like glyburide) for diabetes-can cause dangerous low blood sugar.

Deprescribing: The Art of Stopping What’s Not Helping

The solution isn’t more pills. It’s fewer. Deprescribing isn’t just stopping a drug. It’s a planned, careful process:- Review everything. Get a full list of all medications-prescription, OTC, supplements. Many older adults don’t tell their doctor about the melatonin they take or the ibuprofen they use daily.

- Ask: What’s this for? If a drug was started years ago for a condition that’s now resolved, it may no longer be needed.

- Check for interactions. Some drugs don’t just cause side effects-they make other drugs stronger or weaker.

- Start with the highest-risk meds. Tackle benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and NSAIDs first.

- Stop one at a time. Never cut multiple drugs at once. Monitor closely for withdrawal or rebound symptoms.

- Give it time. Improvement can take weeks. Better sleep, clearer thinking, stronger legs-they don’t happen overnight.

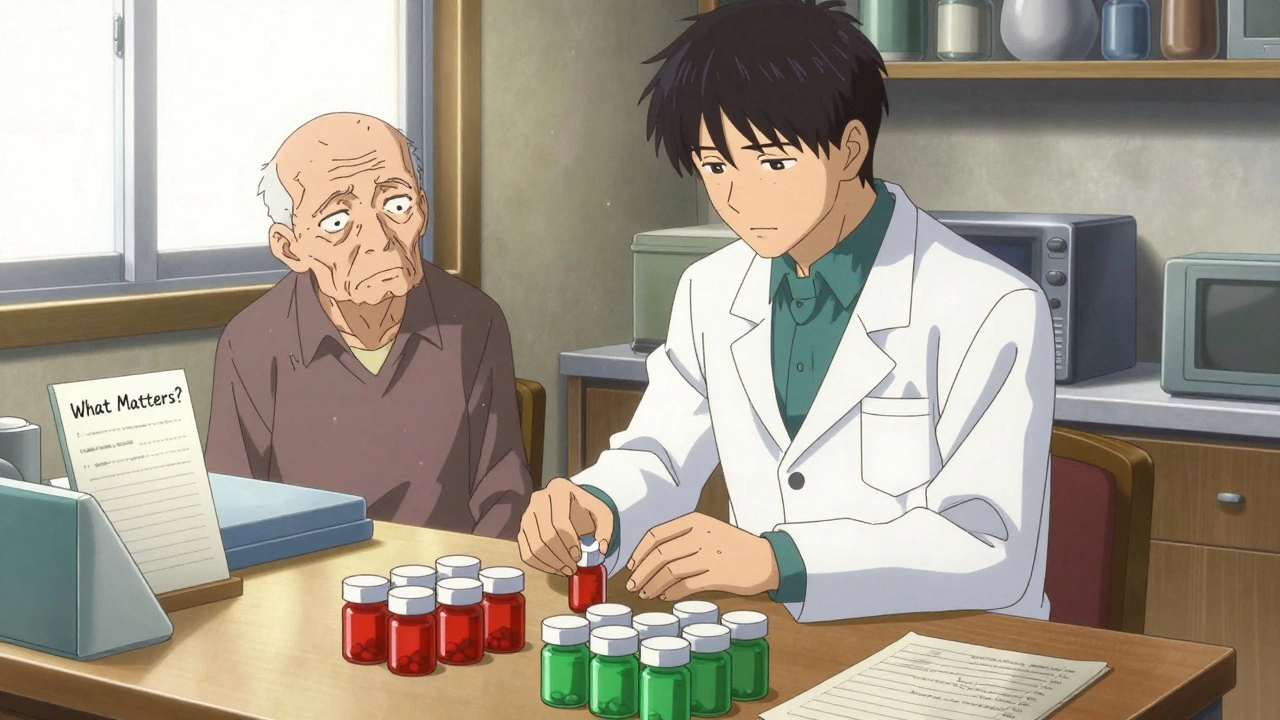

Who Can Help? Pharmacist-Led Care Makes a Difference

Most primary care doctors are stretched thin. They see 20 patients a day. They don’t have 20 minutes to review a 12-medication list. That’s where pharmacists come in. Pharmacist-led medication reviews cut adverse events by 34%. They’re trained to spot hidden dangers. They know the Beers Criteria inside out. They can talk to patients in plain language: "This sleep pill might be making you dizzy. Let’s try something safer." In Halifax, community pharmacies now offer free "Medication Check-Ups" for seniors. No appointment needed. You bring your pills in a bag. They sort them. They flag the risky ones. They call your doctor. In one pilot program, 62% of participants stopped at least one unnecessary drug-and 78% reported feeling more energetic within six weeks.What About the Fear of Stopping?

"What if I get sick again?" That’s the biggest fear. Many older adults believe every pill is a shield. Stop one, and the disease will come roaring back. But here’s the truth: many of these drugs were started to prevent something that never happened. A blood thinner after a minor stroke five years ago? A statin for borderline cholesterol? A sleep aid for temporary insomnia in 2018? The EMPOWER trial showed that 76% of older adults who stopped inappropriate medications did so safely-with no rebound symptoms. And 32% reported better quality of life. They slept better. They walked farther. They stopped worrying about falling. The fear isn’t irrational. But it’s often based on misinformation. A simple conversation with a pharmacist or geriatrician can change that.

Technology Is Helping-But It’s Not Enough

New tools are emerging. The FDA approved MedWise Risk Score in early 2024. It analyzes a patient’s full med list and gives a risk score for adverse events. Hospitals in Toronto and Vancouver are starting to use it. Apps like Medisafe and Round Health help people track doses. But they don’t solve the core problem: too many drugs. The real breakthrough is the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative. It’s not a tool. It’s a mindset. Four questions every provider should ask:- What Matters? What are your goals? To live at home? To walk without help?

- Medication. Are any of these drugs hurting more than helping?

- Mentation. Are you confused or forgetful? Could a med be causing it?

- Mobility. Are you steady on your feet? Could a med be making you unsteady?

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you care for is on five or more medications:- Make a list. Write down every pill, patch, capsule, and supplement. Include doses and why it was prescribed.

- Bring it to your next appointment. Ask: "Which of these can I stop?" Don’t be afraid to say, "I think I’m on too many."

- Ask for a pharmacist consult. Many clinics now offer this for free.

- Watch for changes. Did you feel better after a recent dose change? Did you stop falling after switching sleep meds? Tell your doctor.

- Don’t stop anything on your own. But do ask. The answer might be: "You don’t need this anymore."

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Medication-related problems cost the U.S. healthcare system $30 billion a year. They cause up to 300,000 preventable deaths. And they rob older adults of their independence. But here’s the hopeful part: reducing polypharmacy doesn’t mean giving up on care. It means getting smarter about it. When frail older adults stop unnecessary drugs, they don’t just live longer. They live better. They sleep through the night. They walk to the mailbox. They laugh with their grandkids. This isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about cutting the clutter. So the body can focus on healing-not fighting side effects.Is polypharmacy always harmful for older adults?

No-not all multiple medications are harmful. Some older adults genuinely need several drugs to manage serious conditions like heart failure, diabetes, or epilepsy. The problem isn’t the number of pills-it’s whether each one is still necessary, appropriate, and safe for that person’s current health and frailty level. A 75-year-old with three heart conditions and a pacemaker might need five meds and do fine. A frail 85-year-old with mild arthritis and no heart issues on ten meds likely doesn’t.

Can deprescribing make someone sicker?

Rarely, if done correctly. Deprescribing isn’t about abruptly stopping meds. It’s a slow, monitored process. For example, a benzodiazepine might be tapered over six weeks. Blood pressure meds might be lowered gradually. Studies show that when done with care, deprescribing leads to fewer hospital visits and improved well-being. The real risk isn’t stopping a drug-it’s continuing one that’s causing harm.

Why don’t doctors just stop these medications?

Many doctors want to, but they’re not trained to do it. Medical education focuses on adding treatments, not removing them. Time is also a huge barrier-reviewing a full med list can take 20 minutes, and most appointments are 10. Plus, some doctors fear legal liability or patient complaints if a drug is stopped. But with tools like the Beers Criteria and pharmacist support, it’s becoming easier and safer.

What’s the difference between Beers Criteria and STOPP/START?

Beers Criteria identifies medications that are potentially inappropriate for older adults-like certain sleep aids or NSAIDs. STOPP/START goes further: STOPP flags inappropriate prescriptions (e.g., giving a diuretic to someone with low blood pressure), while START flags missing but needed medications (e.g., a bone density drug for someone with osteoporosis). Together, they give a fuller picture: not just what to stop, but what to start.

How can I tell if a medication is causing side effects?

Look for new symptoms that started after a medication was added or changed. Common signs: dizziness, confusion, constipation, falls, fatigue, loss of appetite, or sudden memory lapses. If a symptom appeared within days or weeks of a new drug, it’s likely connected. Keep a symptom diary. Note when it happens, how long it lasts, and what meds were taken that day. Bring it to your pharmacist.

Are natural supplements safe for frail older adults?

Not necessarily. Many older adults assume "natural" means safe. But supplements like St. John’s Wort can interfere with blood thinners. Ginseng can raise blood pressure. High-dose vitamin E can increase bleeding risk. In fact, nearly 40% of frail older adults take at least one supplement-and many don’t tell their doctor. Always list supplements on your med list. They’re drugs too.

Comments (11)

ian septian

Just had my mom’s med list reviewed by a pharmacist last week. Cut three pills-now she’s sleeping through the night and not falling in the bathroom. Simple stuff, huge difference.

Chris Marel

I’ve seen this with my grandfather. He was on twelve meds. We didn’t know which ones were helping and which were just making him confused. The pharmacist sat with us for an hour, explained each one like we were five. He’s been on nine now. Smiles more. Walks farther. Feels like we got him back.

Carina M

It is profoundly disconcerting to observe the erosion of clinical rigor in geriatric pharmacotherapy. The casual deprescribing advocated herein, while emotionally appealing, lacks the methodological discipline required for evidence-based practice. One cannot simply excise medications without rigorous pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation, particularly in the context of multimorbidity. This is not medicine-it is populism dressed in the lab coat of compassion.

Elliot Barrett

Yeah, sure. Let’s just stop all the meds. Next thing you know, grandma’s having a stroke because we took away her blood thinner. Doctors don’t prescribe these things for fun. You think you know better than a cardiologist who’s been treating her for 12 years? Wake up.

Andrea Beilstein

It’s not about the pills it’s about the silence between them

How many of us are living inside a symphony of chemicals we never asked for

How many of us have forgotten what it feels like to be tired without a pill to fix it

Frailty isn’t the body breaking down it’s the system breaking the body

We treat symptoms like enemies instead of whispers

And then we wonder why people stop walking stop laughing stop remembering who they were before the prescriptions started

iswarya bala

my auntie took off her sleep pill and now she dance with grandkids at night 😍 no more zzzzzz all day! pharmacy help so much!!

Simran Chettiar

One must consider the ontological implications of pharmacological dependency in the geriatric population. The modern medical paradigm has, in its relentless pursuit of quantitative metrics, displaced qualitative human experience. The reduction of polypharmacy is not merely a clinical intervention but a reclamation of agency over bodily autonomy. When we deprescribe, we do not merely remove substances-we restore temporality to the aging self. The pill becomes a symbol of institutional control; its removal, an act of existential resistance.

om guru

Deprescribing is not removing medicine it is removing noise

Listen to the body not the algorithm

Pharmacist is your friend not the doctor who only sees you for 7 minutes

Start with benzodiazepines

Then anticholinergics

Then NSAIDs

Then review

Do not rush

Do not fear

Do not assume

Richard Eite

USA is the only country that lets pharmacists do this right

Other countries? They still let old people die from bad meds because their doctors are too lazy to check

Thank god we got real healthcare here

Not like Canada where they just say no to everything

Katherine Chan

My grandma went from 14 pills to 6 and now she gardens every morning

She says she feels like herself again

Not the zombie version

Just a little more energy

Just a little more joy

It’s not magic

It’s just stopping what wasn’t helping

Philippa Barraclough

While the article presents a compelling narrative around deprescribing, it is worth interrogating the generalizability of the data cited. The Johns Hopkins protocol, for instance, was conducted within a specific institutional context with trained geriatric pharmacists and structured follow-up protocols. In community settings with limited resources, how scalable is this? Furthermore, the EMPOWER trial excluded patients with severe cognitive impairment-does this introduce selection bias? The anecdotal success stories are emotionally resonant, but without stratified outcomes by frailty index, socioeconomic status, and access to follow-up care, the policy implications remain ambiguous.