When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. Often by 80% or more within three years. That’s not luck. It’s predictable. And if you’re a pharmaceutical company, not knowing exactly when that will happen can cost you hundreds of millions-or even billions-in lost revenue. The key isn’t just watching the patent clock. It’s understanding the entire system behind generic entry: the legal hurdles, the regulatory delays, the strategic moves by competitors, and the hidden tactics used to slow things down.

Why Generic Entry Isn’t Just About the Patent Expiration Date

Most people think: patent expires → generics come in. Simple. But that’s where forecasts go wrong. The real timeline starts years before the patent ends. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal pathway for generic manufacturers to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) before the patent expires. That means generic companies can start preparing while the brand drug is still protected. The first company to file a Paragraph IV certification-challenging the patent-gets 180 days of exclusivity. That’s a huge incentive. So instead of waiting for the patent to expire, smart generic makers file early, triggering legal battles that can delay entry by months or even years.Take Humira. Its core patent expired in 2016. But the first biosimilar didn’t hit the market until 2023. Why? Because the manufacturer, AbbVie, built a patent thicket of over 130 patents. Each one was used to file lawsuits, delaying competitors. That’s not an exception-it’s the new norm. In 63% of the top 100 drugs, companies use tactics like "product hopping"-switching patients to a slightly modified version just before the patent expires-to extend their monopoly. These aren’t new drugs. They’re tweaks. But they reset the clock on generic entry.

The Data That Actually Matters

If you’re trying to predict when a generic will launch, you need more than a calendar. You need access to the FDA Orange Book. This is the official list of approved drugs and their patents. But it’s not enough. You also need to track:- ANDA submissions-how many generic companies have filed, and when.

- Paragraph IV certifications-these are legal challenges to patents. Each one is a red flag that a generic launch is coming.

- Patent litigation outcomes-42% of patent disputes delay generic entry by an average of 18.7 months.

- FDA approval timelines-the median time from ANDA submission to approval is 38 months. But if the FDA is backed up (like during the pandemic), that can stretch to 45+ months.

- Therapeutic equivalence codes-these tell pharmacists if a generic can be automatically substituted. If a drug doesn’t have an "A" code, substitution is restricted, which slows price drops.

Companies like Drug Patent Watch and Evaluate Pharma combine these data points into forecasting models. Their best models use 47 variables-including market size, patent density, and litigation history-to predict entry within a 6-month window. Simple models that only look at patent dates? They’re wrong about half the time.

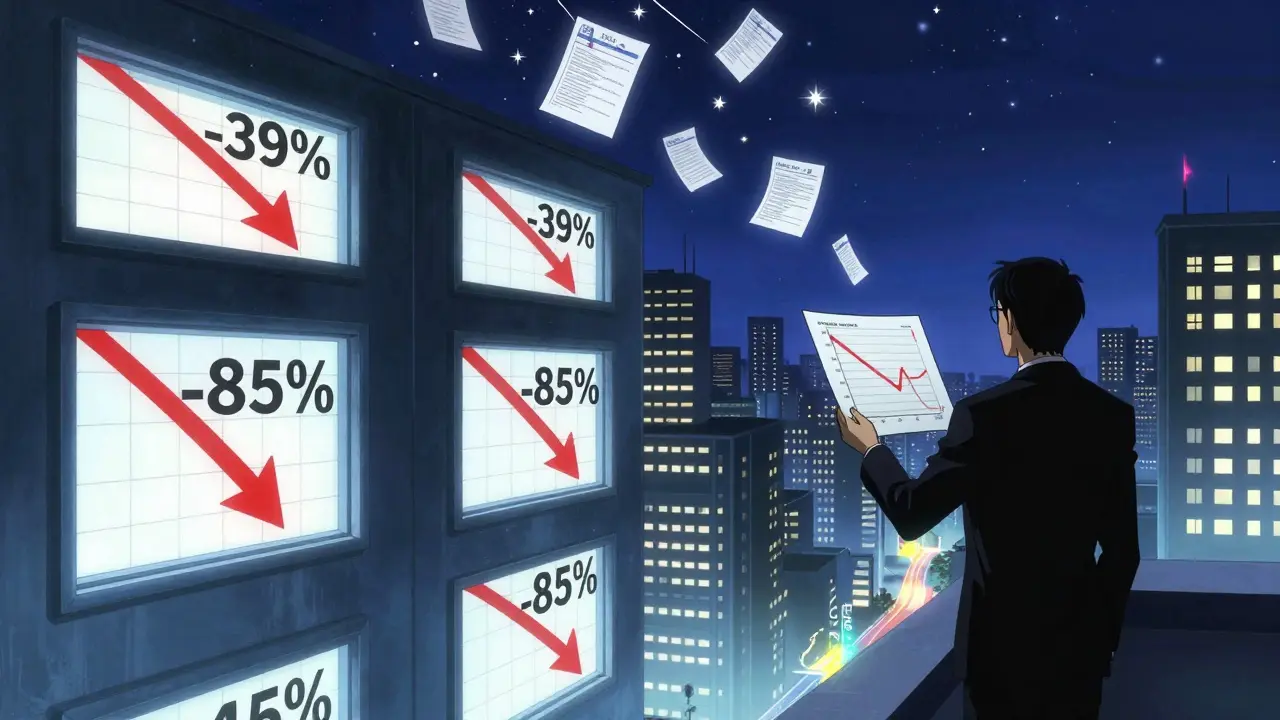

How Fast Do Prices Really Drop?

Once a generic enters, the price collapse happens in stages. It’s not a single drop-it’s a cascade.- First generic: Prices fall 39% below brand level.

- Second generic: Prices drop another 15%, hitting 54% below brand.

- Sixth generic: Prices plunge to 85% below the original brand price.

That’s why the first few competitors matter most. The first entrant gets the 180-day exclusivity and captures the biggest share. The second and third squeeze out the rest of the profit. After that, it’s a race to the bottom. But this only applies to small-molecule drugs. For biologics-like insulin or Humira-the drop is much slower. Because biosimilars are harder to make, and the FDA requires more data, it takes 12-18 months longer to get approval. And even after approval, doctors don’t always switch patients. So prices only drop 25-35% after three biosimilars enter. That’s why biologics are the new battleground.

The Hidden Delays You Can’t Ignore

Even if a generic is approved, it might not hit the market right away. Here are the sneaky delays most forecasts miss:- Authorized generics-the brand company launches its own generic version. This happens in 41% of cases. It kills the first-mover advantage and cuts prices before competitors even enter.

- Citizen petitions-anyone can petition the FDA to delay approval. These delay entry by an average of 7.1 months. They’re often filed by the brand company.

- REMS programs-Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies are safety measures. But they’re often used to block generics. REMS can delay entry by 14.3 months.

- State substitution laws-in California, pharmacists can’t substitute generics without a doctor’s OK. In other states, they can. That means price drops move slower in some regions, even if generics are available nationwide.

One pharmaceutical company told analysts they lost $220 million because their model didn’t account for authorized generics. Another generic manufacturer saved $15 million by using Drug Patent Watch’s bioequivalence predictors to avoid a failed ANDA submission. The difference between success and failure isn’t just data-it’s knowing which data matters.

Who’s Doing This Right?

Top pharmaceutical companies don’t rely on one model. They use a mix:- Patent attorneys-to track litigation and patent challenges.

- Regulatory specialists-to monitor FDA approval timelines and citizen petitions.

- Game theory economists-to model how competitors will behave. Will they file early? Will they settle? Will they wait?

Teams that include all three outperform those that rely on spreadsheets and patent dates. The most successful forecasting teams start analysis 36-48 months before patent expiration. They update their models weekly as new data comes in from the FDA, court filings, and market reports.

Even then, things change. In 2023, the FDA launched the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway, giving 180-day exclusivity to drugs with little competition. That’s a new variable. And the Inflation Reduction Act’s 2025 drug price negotiation rules might make generics less profitable for Medicare patients, which could slow entry. Forecasting isn’t a one-time project. It’s a living system.

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

Mistakes are expensive. A company that thinks a drug will face generic competition in January but it actually hits in July? They’ve overestimated their revenue by 6 months. For a $1.2 billion drug, that’s $600 million in bad planning. They might have kept prices high too long, lost market share, or missed the chance to launch a follow-up product.On the other side, a generic manufacturer that enters too early might get sued. Enter too late, and they miss the 180-day exclusivity window. The financial stakes are massive. The U.S. generic drug market was worth $135.7 billion in 2022. But $37.2 billion in annual revenue is at risk from patent expirations through 2027. The companies that forecast best will protect their profits. The ones that don’t will watch their margins vanish.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond?

AI is starting to change the game. By 2026, machine learning models trained on 15 years of ANDA data are expected to cut prediction errors in half-from 11.4 months to 6.8 months. These tools can read patent lawsuits, FDA letters, and court transcripts faster than any human. But they still miss the human element. Like when a brand company quietly shifts patients to a new drug before the patent expires. Or when a settlement between two generic makers delays a launch.And then there’s the rise of complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, and topical creams. These take 52 months to get approved, not 38. That’s a 35% longer forecast window. And they’re growing fast. If your drug is one of them, don’t use the same model you’d use for a simple pill.

The future belongs to those who combine data with insight. Not just knowing when a patent expires-but understanding the legal chess game behind it.

How long does it take for a generic drug to launch after a patent expires?

It’s not that simple. Even after a patent expires, generics can be delayed by lawsuits, FDA backlogs, or authorized generics. On average, the first generic enters 3-12 months after patent expiration. But for drugs with complex patents or regulatory hurdles, it can take 2-5 years.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs-like pills or capsules. Biosimilars are similar but not identical copies of biologic drugs-like injectables made from living cells. Biosimilars take longer to develop (12-18 months more), cost more to make, and face stricter FDA requirements. Price drops are also slower: 25-35% after three biosimilars, versus 85% for small-molecule generics.

Can a brand company stop generics from entering the market?

Not permanently, but they can delay it. Tactics include filing dozens of secondary patents (patent thickets), submitting citizen petitions to the FDA, launching authorized generics, or settling lawsuits with generic makers to delay entry ("pay-for-delay"). These strategies can delay competition by years, but they’re under increasing legal scrutiny.

Why do some generic drugs take longer to get approved than others?

Complex drugs-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-require more testing to prove they work the same as the brand. These "complex generics" take 52 months on average to get approved, compared to 38 months for standard pills. The FDA also prioritizes simpler drugs, so complex ones wait longer in line.

What’s the role of the FDA Orange Book in predicting generic entry?

The FDA Orange Book lists every approved drug, its patents, and exclusivity periods. It’s the starting point for any forecast. But it’s not enough on its own. You need to cross-reference it with ANDA filings, litigation records, and FDA approval timelines. The Orange Book tells you what’s supposed to happen. The rest of the data tells you what’s actually happening.

How accurate are commercial forecasting tools like Evaluate Pharma or Drug Patent Watch?

The best tools are 80-85% accurate in predicting the timing of the first generic within a 6-month window for small-molecule drugs. For biologics, accuracy drops to 55-60%. They’re far better than simple patent-date models, which are only 40-50% accurate. But no tool is perfect-strategic behavior, like patient migration or pay-for-delay deals, can still throw off predictions.

Comments (15)

Melissa Taylor

The patent thicket strategy is wild-130 patents on one drug? It’s not innovation, it’s legal gymnastics. Pharma companies aren’t selling medicine anymore, they’re selling litigation insurance.

John Brown

I’ve seen this play out with my uncle’s diabetes meds. Brand was $500 a month. Generic? $12. Took three years to hit the market though. All those delays? Real people pay the price in skipped doses and ER visits.

Benjamin Glover

Typical American healthcare absurdity. In the UK, generics hit within weeks. We don’t waste years on patent trolling. This is why the U.S. system is broken.

Raj Kumar

ANDA filings + Paragraph IV = the real game. Most folks think it’s just about patent expiry, but nope. It’s a chess match. I’ve worked in R&D-teams that track litigation trends outperform those who just watch the clock. Big difference.

Jocelyn Lachapelle

Authorized generics are the sneakiest move. Brand company launches their own generic to crush the first entrant. It’s like hiring a hitman to kill your own rival. Brutal but effective.

Michelle M

It’s not just about money. It’s about access. If a kid with asthma can’t get their inhaler because the brand company delayed generics for four years, that’s not business-it’s moral failure.

Lisa Davies

Wow. This is why I stopped trusting pharma ads. 🤯 I thought generics were just cheaper versions. Turns out they’re fighting a war behind the scenes. Mind blown.

Nupur Vimal

Everyone says the FDA is slow but no one talks about citizen petitions. That’s the real delay tactic. Some company files a petition just to stall for 7 months. It’s not even about safety. It’s pure sabotage.

Jake Sinatra

While the data presented is comprehensive, one must consider the ethical implications of prolonged market exclusivity. The fiduciary duty to shareholders cannot supersede the public health imperative. A balanced regulatory framework is essential.

RONALD Randolph

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS LOSING! They let these companies play games with patents, delay generics, and charge $10,000 for a pill that costs $2 to make! It’s theft! And the FDA is complicit! WHERE’S THE OUTRAGE?!?!?!?!?!?

Christina Bischof

I didn’t realize REMS programs were being used like this. I always thought they were just safety tools. Turns out they’re just another way to block competition. That’s… kind of depressing.

Cassie Henriques

CGT pathway is a game-changer. If a drug has little competition, they give 180-day exclusivity to the first generic? That’s smart. Encourages entry where it’s needed most. Finally, someone’s thinking about market dynamics, not just patents.

Mike Nordby

The 38-month median approval time is misleading. In 2022, the FDA approved 90% of ANDAs within 30 months. The outliers-like complex generics or those caught in litigation-skew the average. Don’t treat the median as the norm.

John Samuel

Imagine a world where innovation isn’t held hostage by legal loopholes. Where a drug’s value is measured by its impact-not its patent portfolio. We’re not just forecasting entry dates-we’re forecasting the soul of healthcare.

Sai Nguyen

India makes generics for pennies. Why can’t America just import them? This whole system is a scam designed to protect rich CEOs. We’re being robbed. Wake up.