A pterygium isn't just a spot on your eye-it's a warning sign. This fleshy, wing-shaped growth starts on the white part of your eye and creeps toward the pupil, often because of years spent under the sun without protection. If you live near the equator, surf, hike, or work outdoors, you're at higher risk. It’s not cancer, but it can blur your vision, make contact lenses unbearable, and leave your eye looking red and irritated. The good news? You can stop it from getting worse. And if it does, surgery can help-but not without risks.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

A pterygium is a growth of the conjunctiva, the clear tissue covering the white of your eye. It usually begins on the side closest to your nose and slowly grows inward like a small wing-hence the name, from the Greek word pterygion, meaning "little wing." It’s made of tissue, blood vessels, and sometimes fat, and it can range from a barely noticeable pink bump to a thick, opaque layer that covers part of your cornea.

It’s not rare. Around 12% of Australian men over 60 have it. In tropical regions, rates jump to 23% in adults over 40. Globally, an estimated 15 million people are diagnosed each year. It’s the third most common eye surface disorder after cataracts and glaucoma. Most cases show up on one eye, but about 60% of people in high-UV areas get it in both eyes.

Doctors diagnose it with a simple slit-lamp exam-a bright light and magnifying lens that shows exactly how far the growth has crept onto the cornea. No blood tests or scans are needed. If it’s small and not bothering you, it’s often just monitored. But if it’s growing, causing irritation, or threatening your vision, action is needed.

Why Does the Sun Cause It?

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the biggest known trigger. Studies show that people living within 30 degrees of the equator have 2.3 times higher risk than those farther away. Cumulative UV exposure over 15,000 joules per square meter increases your risk by 78%. That’s roughly the amount you’d get from 40 minutes of midday sun exposure every day for 10 years.

It’s not just beach days. Farmers, fishermen, construction workers, and even daily commuters in sunny cities like Brisbane, Mexico City, or Nairobi are at risk. Even on cloudy days, up to 80% of UV rays penetrate the clouds. Snow, sand, and water reflect UV, making exposure worse.

Some researchers suggest genetics play a role-people with family history are 40% more likely to develop it. But environmental factors account for at least 85% of cases. The real problem? Most people don’t realize their sunglasses or hats aren’t enough. Regular sunglasses don’t always block 100% of UVA and UVB. ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards require lenses to block 99-100% of both. If yours don’t say that, they’re not doing the job.

How Fast Does It Grow?

It doesn’t always grow fast. Some pterygia stay the same size for decades. Others creep forward 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year under constant UV exposure. When it reaches the pupil, it starts to distort your vision. It can flatten the cornea’s natural curve, causing astigmatism. That means things get blurry, especially when reading or driving at night.

Patients often notice symptoms before they see the growth. Constant redness, a gritty feeling like sand in the eye, dryness, or difficulty wearing contact lenses are early signs. Some describe it as a "film" over their vision. If you’ve had these symptoms for months and they don’t improve with eye drops, it’s time for an eye exam.

Pterygium vs. Pinguecula: What’s the Difference?

Many confuse pterygium with pinguecula. Both are linked to sun exposure, but they’re not the same.

- Pinguecula is a yellowish bump on the conjunctiva that never crosses onto the cornea. It’s common in outdoor workers-up to 70% in tropical zones. It rarely affects vision and usually just causes mild irritation.

- Pterygium grows from the conjunctiva onto the cornea. That’s what makes it dangerous. When it covers the cornea, it can change your eye’s shape and blur your sight.

If a growth stays on the white of the eye, it’s likely a pinguecula. If it’s moving toward the pupil, it’s a pterygium. One can turn into the other, but not always. The key difference? Vision impact. Pinguecula? Usually harmless. Pterygium? Can steal your clarity.

Surgical Options: What Works and What Doesn’t

Surgery is the only way to remove a pterygium. But it’s not always recommended. If it’s small and not affecting vision, doctors will suggest UV protection and lubricating eye drops. Surgery is usually reserved for when:

- The growth is approaching or covering the pupil

- You have blurry vision or astigmatism caused by it

- It’s causing constant irritation or discomfort

- Contact lenses can’t be worn

There are three main surgical approaches:

- Simple Excision - The growth is cut out. This used to be the standard. But without extra steps, recurrence rates are 30-40%. That means nearly half the patients get it back within a year.

- Conjunctival Autograft - After removing the pterygium, a small piece of healthy conjunctiva is taken from under your eyelid and stitched over the area. This lowers recurrence to just 8.7%. It’s now the gold standard in developed countries.

- Mitomycin C + Autograft - Mitomycin C is a chemotherapy drug used in tiny amounts during surgery to kill off cells that cause regrowth. When combined with autograft, recurrence drops to 5-10%. It’s used for aggressive or recurrent cases.

A new option gaining traction is amniotic membrane transplantation. In June 2023, European guidelines recommended it as first-line for recurrent pterygium, with 92% success in preventing regrowth based on trials across 15 countries. It uses tissue from donated amniotic membranes to promote healing and reduce scarring.

What Happens After Surgery?

The procedure takes about 30-40 minutes under local anesthesia. You’re awake but feel no pain. Recovery isn’t quick.

- First week: Eye is red, watery, and sensitive to light. You’ll wear a protective shield at night.

- Weeks 2-4: Steroid eye drops are critical. Skipping them increases recurrence risk. Some patients report burning or stinging-normal, but annoying.

- Weeks 5-6: Redness fades, but some pinkness can last months. Most patients say vision improves noticeably by week 4.

Side effects? Pain for 2-3 weeks (42% of patients), temporary dryness, and cosmetic concerns about lingering redness (37%). One patient on RealSelf said: "The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected."

Success rates? Around 87% of patients report "significant relief from irritation" post-surgery. But recurrence is still a problem-32% of people get it back within 18 months if the right techniques aren’t used.

How to Stop It Before It Starts

The best treatment is prevention. And it’s simple:

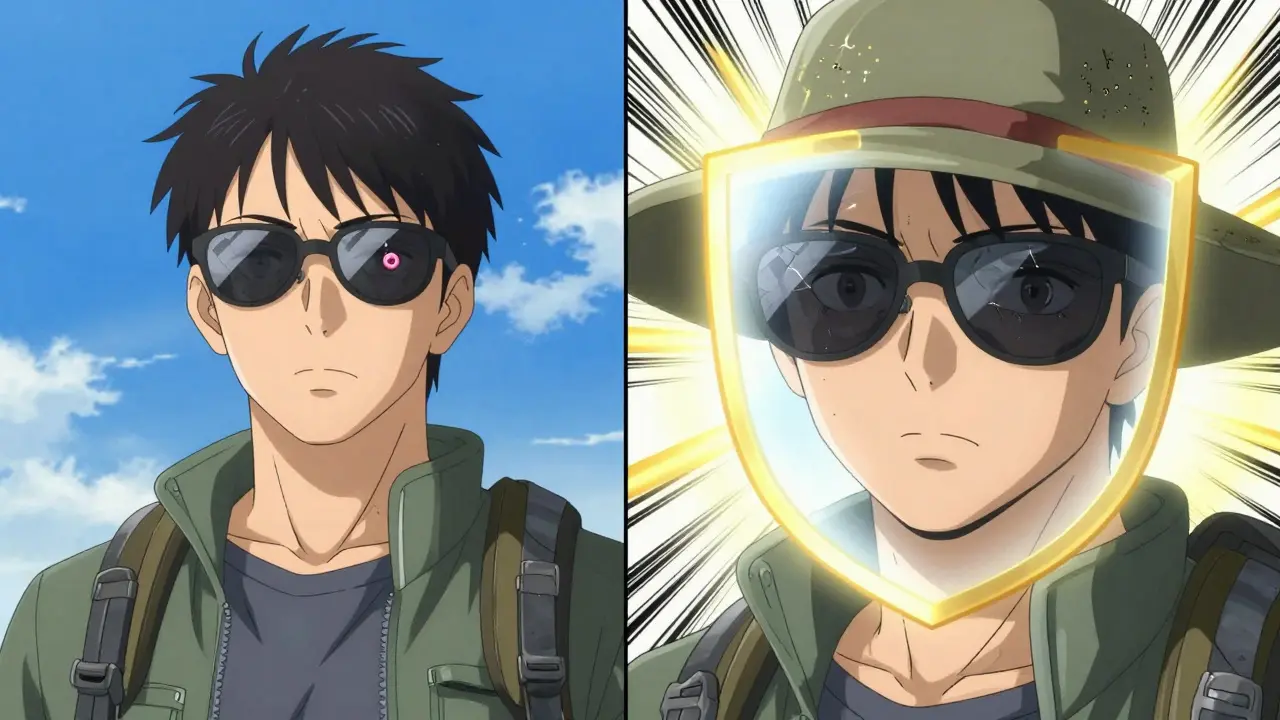

- Wear UV-blocking sunglasses daily - Look for labels that say "100% UV protection" or "meets ANSI Z80.3-2020." Wraparound styles block rays from the sides.

- Wear a wide-brimmed hat - Even a 3-inch brim reduces UV exposure to your eyes by 50%.

- Check the UV index - Protection is needed when the index is 3 or higher. That happens over 200 days a year in equatorial regions.

- Don’t rely on clouds - UV penetrates thin clouds. Your eyes are still at risk on overcast days.

- Use lubricating drops - If you’re outdoors often, preservative-free artificial tears help reduce irritation and dryness.

One Reddit user, "OutdoorPhotog," shared: "Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily has stopped the progression of my early-stage pterygium according to my last two annual check-ups."

There’s also a new product: OcuGel Plus, FDA-approved in March 2023. It’s a preservative-free lubricant designed specifically for post-surgery or high-risk patients. Clinical trials showed 32% more symptom relief than standard eye drops.

What’s Next for Treatment?

The future is looking better. Researchers are testing topical rapamycin, a drug that stops the cells responsible for growth from multiplying. Phase II trials show a 67% reduction in recurrence at 12 months compared to placebo. That could mean less surgery in the future.

Laser-assisted removal is also on the horizon. By 2027, 78% of ophthalmologists expect to use lasers for more precise, less invasive removal. It’s not here yet, but it’s coming fast.

Still, access is unequal. In rural areas of developing countries, only 12% of people can get surgery. In cities of developed nations, it’s 89%. That’s a gap that needs closing.

Final Thoughts

Pterygium isn’t a life-threatening condition, but it can steal your vision-and your comfort. If you spend time outdoors, especially under strong sun, your eyes need protection like your skin does. A pair of proper sunglasses and a hat aren’t fashion choices-they’re medical tools.

If you already have it, don’t panic. Monitor it. Protect it. See your eye doctor yearly. Surgery works, but only if done right. And prevention? That’s the easiest win of all.

Comments (1)

John McDonald

Been surfing for 15 years and never wore proper shades till I got my first pterygium. Now I’m all about the wraparounds with ANSI Z80.3-2020 labels. My eye doctor said if I’d worn them from day one, I might’ve avoided it entirely. Don’t be like me-learn the hard way.